The California accountability system’s interpretation of the progress of English learners is wrong. That’s the bad news. Its flaws are explained in a recent article, “Hidden Progress of Multilingual Students on NAEP.”* that appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of AERA’s bimonthly journal, “Educational Researcher.” The irony is that we are missing a happy conclusion. If we look at students who were classified as English learners at any time as the group worthy of measuring, we would see they are making progress in ELA and math at a faster pace than their monolingual, English-only peers.

Here’s the good news: they’re doing much better than we’d thought.

Here in California, we’re accustomed to seeing students who are English learners grouped as one category and lagging far behind their grade level peers all the time, in every category. This apparent bad news recurs year after year. And every year Californians conclude that educators are failing to adequately educate students who are English learners. Is it possible we have been lulled to sleep? This journal article is quite a wake-up call.

The researchers, Michael Kiefer (New York University) and Karen Thompson (University of Oregon) draw their conclusions after banging on data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (known by its acronym, NAEP, and as the nation’s report card) from 2003 to 2015. They ask a question about semantics: “Why do we call students who have command of their first language and partial mastery of English simply “English learners?” These students are, indeed, learning English. But they are closer to becoming bilingual than students who have grade level mastery of English alone.

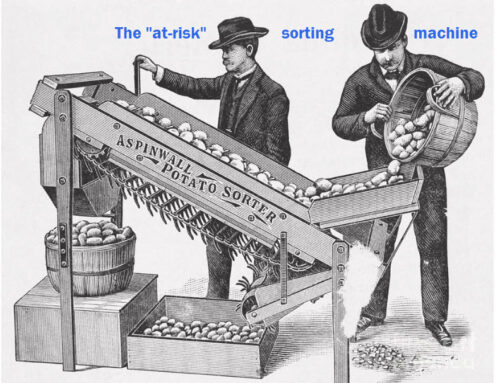

But Kiefer and Thompson also ask a second question about the illogic of measuring students who are labelled as belonging to a category whose members, by design, are changing all the time. They propose what some in California have finally come to embrace, that we look at students who were at any time classified as English learners (the “Ever EL” category). Many other scholars have raised this question, most recently Paul Warren, from the Public Policy Institute of California. (See Paul Warren’s report recap in my blog of July 2018.) What makes Kiefer and Thompson’s question so important is that they propose a fix, using the data that’s already in their hands and ours.

Kiefer and Thompson used the NAEP data (the Nation’s Report Card) to cobble together those students who have been reclassified as Fluent English Proficient students (RFEP in California) with those who are still classified as English learners and looked at their results. Here’s what they found:

“Between 2003 and 2015, NAEP achievement differences between monolingual and multilingual students have narrowed between 24% and 27% in reading and 37% and 39% in math. In grades 4 and 8 respectively…. When converted into grade equivalents, these changes indicate that multilingual students are about one-third to one-half of a grade level closer to their monolingual peers in 2015 than they were in 2003.

Although monolinguals’ scores have increased significantly over time, multilingual students’ scores have increased substantially more across both grades and subjects – nearly twice as much in grade 4 in both reading and math, more than three times as much in grade 8 reading, and more than twice as much in grade 8 math.

Mind you, these are cross-sectional views of progress. I can only wonder what a quasi-longitudinal view would show of a graduating class cohort’s rate of progress.

The level of EL achievement we Californians are accustomed to seeing is perpetually low. But this is based on an incorrect framing of the group to be measured, and a misunderstanding of the meaning of the data the state assessment produces. How ironic that the problem is really the deficient logic and semantic confusion of educators.

We have seen in California the common occurrence of exceptionally high scores of RFEPs for years, both in the CST era and now. But what we have not seen (because we have not cared to do so) is how the year-to-year results of ELs would look if we joined the results of RFEPs together with the results of those we still categorize as ELs, and look at this entity as one.

It’s about time we did just that. Rather than wait for the CDE and the State Board to do this, we will do so ourselves and share results with you soon. Unraveling the semantic confusion and illogic that compromise the state accountability system’s dashboard has been our focus since 1998. False modesty aside, I think our 20 years of experience in the accountability wars gives us the battle scars and experience and knowledge necessary to do this right.

But let’s call attention to the other side of Kiefer and Thompson’s findings. They argue that it is both fairer and more accurate to think of English learners as partially multilingual students already. They have some degree of mastery of English. Perhaps it is the ability to speak and understand English on the playground. Perhaps it is their partial ability to read academic English at grade level. The point is that they are part way toward being multilingual-capable students. Why not categorize them in a way that describes the language skills they’ve gained rather than those they lack?

If we consider that a valid entity, then let’s use it, and compare the achievement and progress of students who are multilingual with those who are monolingual.

To read other blog posts on the errors and illogic of the California Dashboard, click here.

___________________

* Kieffer, M. J., & Thompson, K. D. (2018). Hidden Progress of Multilingual Students on NAEP. Educational Researcher, 47(6), 391–398. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X18777740