Today we know less about California schools than we knew ten years ago. The list of data missing in action includes data about courses taught, class sizes, teachers and administrators, student-counselor ratios, librarians and the college-going rate of high school graduates. As a result, Californians are no longer able to answer questions like these:

- What is the ratio of students-per-counselor in our high schools and how does that compare to high schools statewide?

- How many middle schools in our county have librarians?

- What is the average class size of our high school core courses, and how does that compare to the state average?

- What proportion of our high school graduates in the Class of 2021 enrolled in two-year and four-year colleges and how does that compare?

- Is our district offering fewer foreign language or AP courses compared to other districts our size?

- What portion of our teachers who work with emerging bilingual students (ELs) have the right credential to do so?

This data void leaves districts without the ability to compare

District staffers, mainly CALPADS administrators, have been shoveling this data to the California Department of Education for years. No small amount of human effort is invested in moving mountains of data about 275,000 teachers and 265,000 classified staff hither and yon. But it can’t benefit anyone if it doesn’t get published.

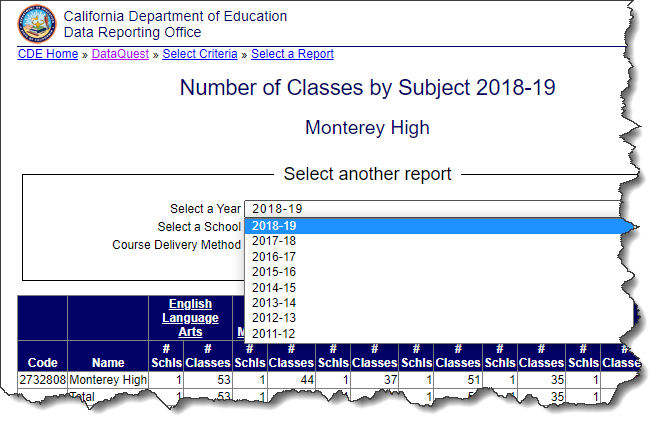

This is a DataQuest screen captured on May 19, 2023, showing course-offering data only up through the 2018-19 school year. No data on classes or courses has been published from 2020-2023 school years.

The irony is that every district has the ability, of course, to answer these questions about their own organizations. But they are unable to compare their own district to any other. This leaves them with descriptive data that lacks comparative context. Without context, how are you to make sense of it?

Of course, this leaves legislators, advocates, policy analysts and researchers in the data-less zone, as well. When district and union bargaining teams sit down to examine working conditions, they’d certainly want to compare class-size data with benchmark districts. The last year you could answer that question: the 2018-19 school year. (I have a stake in this data, too. I lead a team, the K12 Measures Project of School Wise Press, that depends on this data to create comparative visual evidence for site and district planning teams.)

The college-going data about the state’s high school graduates was last available for the 2019-20 school year. Why is it lagging two years? The data is in the hands of the National Student Clearinghouse. All that’s needed is for the CDE to license it. In fact, some districts do this on their own because they value the information so highly. Many states report this information. Why not California? Looking for SAT, ACT or Advanced Placement results? You’re out of luck. But in 2016 you’d have found them easily.

The CDE’s reasons for stopping support of data

Why have the CDE higher-ups stopped publishing these vital data? Preceding generations of CDE leaders were proud of their work as stewards of these public data assets. I’ve asked Cindy Kazanis, the CDE’s director of the Analysis, Measurement & Accountability Reporting Division more than four times, and was told that they no longer support these data because demand for them isn’t evident.

Really? The teacher unions and district management don’t need class-size data to compare working conditions among districts? The social justice advocates don’t need to know which districts have more crowded classrooms? The children’s advocacy groups like Children Now don’t need to know which schools don’t have libraries? Youth advocacy groups and parents don’t care about the case-load of counselors in their local high schools? ACSA and CSBA don’t care about comparative course-offerings, as the staffing squeeze on middle and high schools gets tighter? Doesn’t Linda Darling-Hammond and the State Board of Education care about this cloud of fog that is making it harder and harder for the public to see its schools fully in the light of day?

This leads me to wonder how detached from public opinion the CDE staff and their leader, SPI Tony Thurmond, can be. With annual surveys of Californians in hand from the Public Policy Institute of California that make visible what parents want to know about schools, the CDE leadership cannot claim to be unaware of what the public needs to know. With talk in Sacramento now about making the superintendent of public instruction a governor-appointed position, Tony Thurmond would do well to pay greater attention to the public’s right to know their schools’ and districts’ vital signs.