Today, California’s Dept. of Education fields a test (CAASPP) that educators are told is good for almost everything. Like the Veg-O-Matic, a kitchen appliance sold on television in the 1960s, its promoters claim it is good for finding out to what degree classrooms, schools and districts full of students in grades 3-8 have reached grade level mastery of reading, writing and arithmetic. The CDE higher-ups also claim it’s good for estimating individual students’ mastery of reading, writing, math and science, and is therefore useful to teachers in guiding instruction.

Whee! The ebullient claims of Veg-O-Matic tv saleswomen are ringing in my ears: “It slices! It dices!”

But with only 17-23 questions presented to students in grades 3-8, I am skeptical that the CAASPP can deliver classroom level or student level results with reasonable precision and certainty. (Click here to see the math blueprint and here for the ELA blueprint.) I am eager to see the CDE reveal the degree to which imprecision and uncertainty have grown larger as a result of cutting in half the number of multiple choice questions. I am not persuaded by the claim made in 2021 by Mao Vang, who heads CDE’s Assessment Development and Administration Division, that this halving of the multiple choice questions comes at no cost to accuracy of results. Her comments, quoted in EdSource, feel like a parent’s reassurance to a child – both condescending and hollow.

The assurance offered by Mao Vang was also disputed by Doug McRae, a veteran psychometrician whose four-decade-long career in educational measurement included being vice-president of the testing firm, CTB-McGraw-Hill, and advisor to CDE on the STAR assessment which ran from 1999-2013. His comment on the EdSource article was blunt. “The statement that ‘scores will be just as accurate,’ attributed to Mao Vang, is not accurate. The accuracy of test results is commonly measured via what is labeled ‘reliability’ by educational measurement experts, and formulas for reliability depend on the number of test questions included in the test.”

How exactly should charter authorizers use CAASPP results?

The CDE uses CAASPP for many purposes: determining if a school needs technical assistance; determining a school or district’s place on the Dashboard; determining if a district qualifies to apply for competitive grants; and more.

But I want to question one particular use of CAASPP results: evaluating charter schools. What, exactly, is the soundness of the results from CAASPP when making inferences of a life-and-death nature about a charter school’s renewal?

Soundness depends on many factors. One of them is how many students are enrolled, and how many of them took the CAASPP. But another is how many questions those students answered. Today, for students in grades 3-8, the CAASPP math and ELA tests remain in their half-sized form, and present 17-19 multiple choice questions to test takers, depending on their grade level. Students also face a few performance tasks (between one to four) that require writing. Adults score those performance tasks on a scale from 2 to 10.

The COVID era was the initial reason for shrinking the test to roughly half its prior size. Reducing the time required for student test-taking and reducing test fatigue was the goal. Now, having faced pressure from teacher unions and anti-testing forces, the CDE has extended this shrunken test. But at what cost to imprecision? At what cost to uncertainty?

For now, if I were a charter authorizer I would take CAASPP results with a grain (or a rock) of salt. That is, I would only consider scale score results as a range adjusted by the imprecision (“standard error” in stat-talk), rather than a point score.

So many standards. So few questions.

Will the CAASPP questions test what students were taught? Maybe. But with standards already a mile wide, it’s simply luck that determines if the standards that students learn are the standards that are tested. Whatever luck was needed in the prior era, when the number of multiple choice questions on the CAASPP numbered 35-45, much more luck is needed with a test that includes just 17 multiple choice questions.

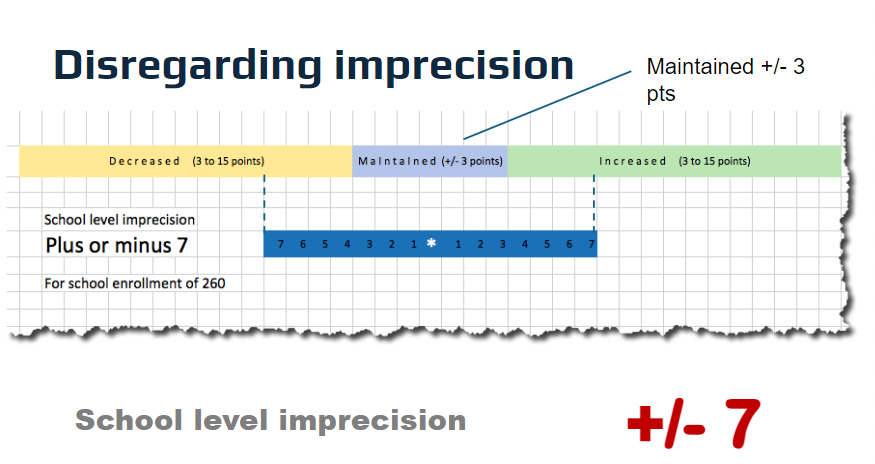

The Dashboard’s change-from-prior-year has little relevance to a school with 260 kids who are tested. The imprecision of CAASPP could span three zones: decreased, maintained and increased.

Seventeen multiple choice questions will unavoidably widen the degree of imprecision in results. Even before the COVID era, the imprecision for a school of 270 kids was expected to range +/- 7 to 9 scale score points. How much bigger does that imprecision grow with a test half that size? The uncertainty is considerable. Roughly two out of three times, the imprecision will fall within that range. One out of three times it will fall outside it. Charter authorizers and the boards of charter schools that rule on renewal petitions need to know this. And they need help knowing how to act on both the imprecision and uncertainty that are an unavoidable element of the score’s meaning.

Come, on CDE. Stop selling educators a Veg-O-Matic, and start sharing the nitty-gritty facts about the increase of imprecision and uncertainty that the abbreviated CAASPP results contain. At the student level. At the classroom level. At the school level. If you are insisting that charter authorizers base their judgments about charter schools’ academic effectiveness on the CAASPP, you owe those authorizers more than a four-digit scale score. You owe them a full disclosure of the imprecision and uncertainty of that scale score, so they can make a reasonable judgment.

[Thanks to Chris Moggia, assessment chief at PUC and founder of School Data Leadership Association, for calling this question to my attention.]