“The key question is whether teaching can shift from an immature to a mature profession, from opinions to evidence, from subjective judgments and personal contact to critique of judgments.” — John A.C. Hattie, Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, Routledge (2009), pg. 259.

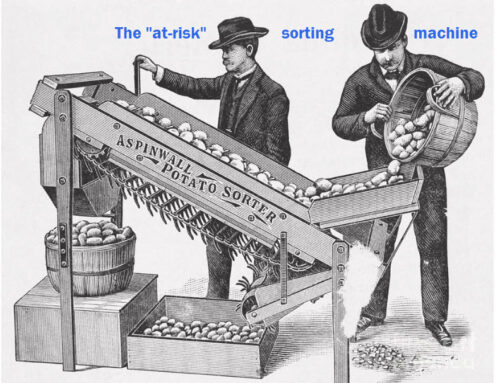

I am no longer surprised when reading California school districts’ Local Control Accountability Plans to see goals projected as a straight line sloping upward. Five percent better, each year for three years. Like stair steps, an equal amount of progress with every step. It doesn’t matter what aspect of schooling is the object of this forecast: graduation rates, test results, achievement gaps. Planners all seem to share a belief that progress will result, and it will come in even increments. I have a name for this approach: faith-based planning.

When those forecasts fail to come true, I wonder if anyone is surprised. I wonder if the cabinet level leaders in the district who reviewed site plans stopped to ask if those ruthlessly regular steps of promised improvements met the criteria of S.M.A.R.T. goals — a method that many districts have embraced. This acronym stands for “specific,” “measurable,” “attainable,” “realistic” and “time-bound.” At the very least, this straight-line forecast method deserves to be seen as failing the fourth test. Straight lines are not realistic.

Change in percentage of Calistoga Joint USD’s students’ meeting math standards, grades 3-8, from 2010-2018. Vertical scale measures percentage points of change from prior year in students meeting standard. Horizontal black line indicates state average change in percent of students meeting standard. Orange dot represents Calistoga Joint USD’s students. Other dots represent districts with students highly similar to their own.

How do I know? For more than 20 years, I’ve looked at patterns in the vital signs of schools and districts. I led a team of people doing accountability reporting, built an assessment consultancy, and then the K12 Measures group, that is helping those of you leading and governing districts to measure the right things, the right way.

Schools’ vital signs move up and down

I am here to remind you of what you already know. Life is messy. Kids are erratic. Their skills and knowledge grow in fits and starts. These realities don’t result in data points that can be connected with straight lines. They result in zigs and zags, movement up and down. This volatility is expected by social scientists, parents, statisticians, epidemiologists and others who chart what happens with kids. Why have so many educators not accepted this fact of life?

My hunch is that those who lead schools and districts come to planning as a faith-based initiative. After decades of working in a profession that rarely taught the fundamentals of planning or educational measurement, or required administrators to master the standards for data use, how in the world could education leaders be expected to plan properly? Having faith is a good thing, of course. Believing that your teachers could improve, and that students could learn more deeply and more effectively, is essential. But that faith should not result in plans that call for a steady 3 percent gain in students meeting their grade level math standards.

Steps toward ending faith-based planning

The silver lining in this dark cloud is that when you’re this far behind, there’s so much you can do to catch up. I have a few suggestions.

First, require that those with planning responsibility look at the historical evidence. Indeed, looking backward at evidence of prior patterns is a first step in appreciating the future variation of your schools’ or district’s vital signs.

Second, proceed with care as you attempt to infer progress. Be especially careful that you know who you are measuring. Even now, five years after the CAASPP/SBAC replaced the CST and brought us vertically equated scale scores, and the opportunity to look at change across grade levels and draw reasonable conclusions, California’s official accountability system still looks at progress in the old way. Taking all students who were enrolled in your middle school last year in all three grade levels, and comparing them to all students enrolled in your middle school this year means one-third of your students are different. If students were identical, that would be okay. But they’re not identical. What you should be doing is restructuring test results quasi-longitudinally to regard the change in year-to-year results for the same students.

Third, invest in the planning skills of those site and district leaders who you task with planning responsibility. I would bet that no one in your planning teams has studied planning, unless they were graduates of a master’s program in public administration or business. Planning can be learned, but like all craft skills, no one is born possessing those skills. I’ve known one district, Vista USD, to take planning seriously enough to put someone in charge of it. If you know of others, please tell me about them. (Okay. Time to declare my self-interest. Our team is ready, willing and able to help you accomplish all three of these steps, and more. Click here to learn how we do that. I’d welcome your call.)

But now that districts have the mandate to plan openly, in many ways freer of bureaucratic constraints than before, wouldn’t it be great to build plans that earned praise. So many citizens see these plans. So many more parents can see what districts care about most. Isn’t this an ideal moment, then, for district leaders to take planning as seriously as other professions, and elevate the skills of planners to the highest level possible?