Could we get “real” on the topic of planning? Planning in too many districts is a rote exercise to give higher-ups the paperwork that is required by state and federal law. It is too often a cut-and-paste compliance festival designed to exhaust the readers of those plans with over a hundred pages of numbers and words that too often sound like they’ve been created by an AI text-generating engine. [Click here to see the site plan I generated using ChatGPT.]

Good Questions Reveal the Flaws of Bad Plans

If those responsible for reviewing and approving site and district plans were more skeptical, they might ask questions like these:

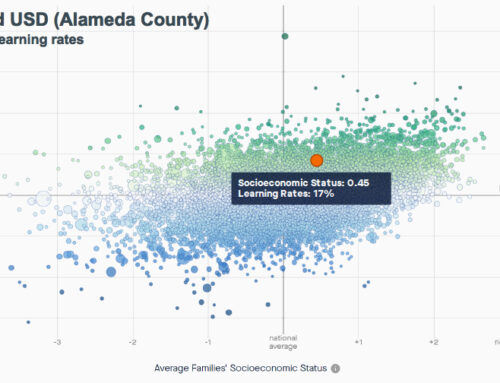

“How are we doing at teaching reading, compared to other schools with kids like ours?”

“How do we know that’s true?”

“If we’re doing okay, why are one-third of our third-graders scoring in the bottom proficiency band on the ELA test?”

“Why are our kids’ math scores for the Class of 2030 well above the state average scale score when they’re in 3rd grade, yet tanking to well below the state average scale score when they complete 6th grade?”

In California, where reading is taught in most districts using curricula that adhere to the widely discredited Balanced Literacy methods, evidence of failed reading instruction is everywhere. Like gold nuggets discovered at Sutter’s Mill, they sit on the ground in plain view. Yet, few of the plans I’ve read even mention the possibility that a school or district may be teaching reading the wrong way.

I have reached this conclusion after having read many dozens of districts’ LCAPs, and too many schools’ SPSAs. I have also read the criticisms of LCAPs shared by superintendents with researchers in the 2018 “Getting Down to Facts II” report. I have also read the Legislative Analyst Office (LAO) 2020 report on the topic of LCAPs. My work for the past nine years has included building evidence for planning teams and teaching them how to interpret that evidence. So I have done my homework.

Forced Optimism: Stalin’s Five-Year Plans, SPSAs and LCAPs

Forced Optimism: Stalin’s Five-Year Plans, SPSAs and LCAPs

Honestly, I feel the pain of principals and district leaders when they complain of their boss’s insistence that their plans promise gains, growth and improvement. Too many superintendents are telling their exec cabinet what they want to see in site plans and the district’s LCAP: “Always up, up, up. Continuous improvement, you know, means every year a little better.” (The Carnegie folks’ model of continuous improvement is a sound one, but its name has led many education leaders to misunderstand it as a Dale Carnegie course in positive thinking.)

This unflagging insistence on progress reminds me of Stalin’s Five-Year Economic Plans. His plans commanded the managers of factories and farms to boost production, and no excuses were allowed. Stalin believed that catching up with the industrial capacity of the capitalist world was essential to the survival of the Soviet Union. His commands to increase productivity by 350 percent in heavy industry between 1928 and 1933 were not taken lightly. Factory managers had ways of boosting output that were sometimes clever evasions of these unrealistic expectations.

Like Soviet managers of that era, district and site leaders have no control of their raw materials: money, tools and people. Nor do they have control of their customers. Schools and districts teach whoever attends. Their employees’ job rights prevent education managers from choosing who to lay off when budget cuts require trimming. And in this era of teacher shortages, I hear stories of HR departments hiring anyone who can fog a mirror.

To expect leaders to plan without having control of their resources and inputs, and then expect them to produce steady gains in outputs, is both laughable and dangerous. One laughs to keep from crying. The danger is in fostering bureaucratic gamesmanship – constantly generating optimistic predictions regardless of the real circumstances, and denying evidence of instructional failure, even those as obvious as sixth-graders reading at a second-grade level.

Desperately Seeking Dissenters from Faith-Based Planning

Do middle school principals agree to boosts in students’ math test scores because they have improved who’s teaching, or how they teach math, or how much of the day is allocated to teaching math? No, they too often surrender, and agree to plug growth numbers in the “goal” part of their Single Plan for Student Achievement to meet their boss’s instructions to “align” the site plan with the district plan. Get out those smiley-face stickers.

If you work in a district where principals have pushed back at the expectations of leadership to boost test results, please let me know. If your district’s LCAP team has resisted the bureaucratic smiley-face pressure to predict growth in test scores, and decreased gaps in everything, I’d love to hear anecdotes of refuseniks. Districts where people are debating what constitutes a reasonable expectation would earn my applause for integrity. (write to me at: steve.rees@schoolwisepress.com)