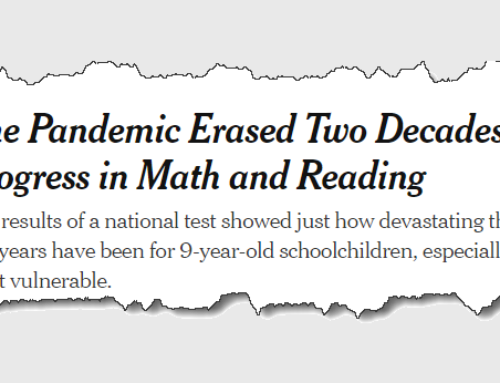

I spent the afternoon of February 12 at Stanford to attend an education research conference hosted by Sean Reardon’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. The room was filled with scholars – visiting faculty, resident faculty and Stanford grad students. All were hungry to either learn or share what they’ve learned. I was excited to be among more than 120 talented and energetic grad students looking for challenges to tackle. Mike Kirst, the executive director of the State Board, was there, too, not to present but to listen and learn.

I listened to three presenters, all centered on the problem of growing inequalities. Ann Owens, from University of Southern California, looked at the relation of inequality to housing segregation, and the effect of both on academic outcomes of students. Another, Ilana Umanski, from University of Oregon, shared her findings on the misclassification of students who are English learners, and the effect of classification errors on student self-perceptions. Kenneth Shores, from University of Pennsylvania, probed the question of how districts’ sorting of students contributes to inequitable distribution of learning opportunities.

With questions so relevant to California, I couldn’t help but wonder how their work would ever end up in the hands of the practitioners who need it most. Why are those who manage curriculum and instruction in district offices so far away from the findings that might enable them to make wiser choices? Is there a bridge at all between researchers and practitioners?

Is the research itself not relevant? I don’t think so. Are administrators no longer hungry for new ideas? Are they reading the publications their professional associations publish which should carry news of this research? Are they even reading their weekly of record, Education Week? Or are they simply pinned down in position, short of time to explore, and short of funds to invest in a day’s visit to a rich conference like this?

I don’t know the answer. But I have informed hunches from my 22 years of observing those whose profession is education management. (And before this blog entry is over, I’ll have a suggestion to try something new.) I have come to watch two phenomena unfold at a slow pace that may help explain the weak bridge between those who run schooling and those who study them.

One trend is the gradual disappearance of program evaluators from the district office staff of larger districts. They have gone the way of the school librarian. They are an endangered species. Nearly extinct.

The other trend is the decreasing status associated with the measurement of learning. Assessment directors, too, have become an increasingly rare species in districts of any size. Their bosses too often treat them as if they are supervisors of a shipping/receiving dock, tasked with receiving test booklets or test forms, and distributing them to their intended recipients. And if they succeed at rounding up all the booklets and test forms they received at the end of the cycle, they are considered to be successful. If they administer an assessment using computers and the requisite software, with no crashes or security violations, then the are deemed to have had a great year.

Both phenomena indicate a decline of analysis in the central office, and the triumph of practitioners. It represents the dominance of knowledge acquired by experience, and the decline of knowledge gained by analytic reasoning. It represents a victory for tradition, orthodoxy and “common sense,” and a loss for the forces of new ideas, evidence-based insights and empirical reasoning. In case I needed a reminder, just recently an assistant superintendent in a county office of education told me excitedly that her team was “moving beyond analysis and moving into action now.” Watch out. Here she comes, driving her county office with eyes wide shut.

In this era when everyone is measuring everything, I believe that those who continue to denigrate knowledge gained by analytic reasoning will learn nothing from their efforts. But those who build room at the table for analysts and the “numbers way of knowing” will benefit quickly as they recognize wasted effort and lost dollars, and steer a smarter course.

My recommendation … those district management teams that welcome analysts should go to their local colleges or universities and ask for help. Don’t just turn to the school of education. Knock on the doors of the business school, the school of public administration, and the schools of economics, information science and social science. Put those students to work in your front office, give them meaty problems to chew on, and then prepare for some old problems to surrender to new attacks. Progress awaits.