Lagging readers are visible in every school and district. But how many of your second- or third-grade students are lagging one year or more? If your answer is about 20 to 30 out of every 100 third-graders are behind grade level by a year or more, I would not be surprised. But would you be surprised to discover that half of them are likely to have biological barriers to learning to read?

Their brains make it hard for them to associate letters they see with the sounds they hear. For the past hundred years, doctors and psychologists have named this phenomenon “dyslexia.” It is the most frequently occurring learning disability in the world. Between 7 to 15 percent of all people have brains that work this way. Some believe it’s 15 to 20 percent, depending on the language they speak.

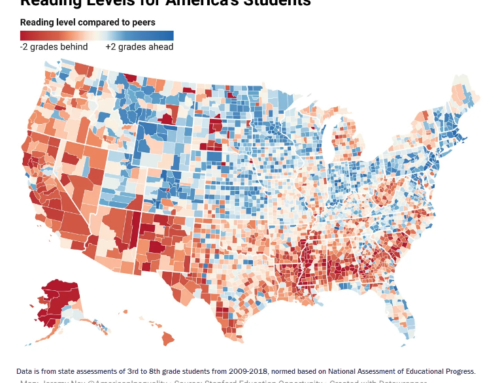

In 39 states, schools must screen for dyslexia. And when they discover students who are to some degree dyslexic, they teach them to read in a different way than other students. Teachers give them a much more intensive dose of phonics, and work much harder at building their phonemic awareness. But 11 states don’t require that districts screen for dyslexia, and California is one of them. Yes, our not-so-golden state, the state that thinks itself to be oh-so-innovative is in fact a laggard. (California’s fourth-graders also lag in reading, ranking 41st on the NAEP, the nation’s report card.)

Good news: nothing is stopping you from screening for dyslexia

The good news … you don’t need to wait for California’s legislature to pass a law to mandate that your district screen all students for dyslexia. You can simply start doing it yourself, voluntarily. Many districts’ coffers are overflowing with pandemic related federal funds. This would be one way to put those funds to work.

More good news … half of your struggling readers would be likely to be identified as dyslexic. If 30 percent of your third-graders are reading well below grade level, and 15 percent of all people are dyslexic, then do the math (15/30 = ½). So you could teach them in ways that take their learning disability into consideration. That would not only enable them to make faster progress toward grade-level reading. It would enable your Tier 2 reading specialists to focus on the students who have no biological obstacles to learning to read, but have not yet been taught to do so. This group suffers from a different problem: dysteachia. That’s your district’s riddle to solve.

More good news … half of your struggling readers would be likely to be identified as dyslexic. If 30 percent of your third-graders are reading well below grade level, and 15 percent of all people are dyslexic, then do the math (15/30 = ½). So you could teach them in ways that take their learning disability into consideration. That would not only enable them to make faster progress toward grade-level reading. It would enable your Tier 2 reading specialists to focus on the students who have no biological obstacles to learning to read, but have not yet been taught to do so. This group suffers from a different problem: dysteachia. That’s your district’s riddle to solve.

Some states have solved that riddle. Mississippi is one of them. They put a stake in the ground, passing a law in 2013 that made Structured Literacy their state’s way to teach reading. And the result? Between 2013 and 2019, the state moved from 39th to 2nd in the fourth-grade reading score rankings of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, what we call the Nation’s Report Card. In 2019, Mississippi was the only state to show an improvement in fourth-grade reading on the NAEP.

Bad news: CTA and CSBA oppose a bill that requires dyslexia screening

The bad news … there’s a bill stuck in the Assembly Education Committee that would require California districts to screen for dyslexia. It is SB-237, authored by Portantino. Although the bill is favored by 87 percent of 4,200 voters polled by EdVoice, SB-237 faces opposition by the CTA and CSBA. Their reasons differ somewhat, but share two objections: (1) that districts would have to pay for this out of their general funds; and (2) that screening would disadvantage non-English speakers – either by over-identifying them or under-identifying them. Both objections are balderdash. Dyslexia screening is not expensive and should be paid for out of general funds. But dyslexia screening can be done in ways that account specifically for the first-language preferences of students.

In fact, in 20 minutes time I discovered three research papers on the effectiveness of different approaches to dyslexia screening for both bilingual students and those who are Spanish-speakers or speakers of other languages. All three articles point not only to viable methods of dyslexia screening. The earliest paper, published in April 2016, focused on dytective, a game-based approach to dyslexia screening that in field testing 243 students — some monolingual English or Spanish speakers, some bilingual, and some diagnosed with dyslexia and others with no diagnosis — they attained an 86 percent accuracy rate. [1] For good measure, a follow up to this study written by many of the prior study’s authors was published about four years late, in December 2020 in the prestigious Public Library of Science. [2] This study looked at 3,600 students, and using an improved method of identifying dyslexia attained an 80 percent accuracy rate.

CTA and CSBA are either unaware of this, in which case they are simply ignorant. Or they are playing the “equity card” out of fear that identifying dyslexic students would lead to a spike in the cost of special education, in which case they are merely cynical and self-interested.

The cost of not screening California kids in grades K, 1 and 2: about $350 million a year

The flaw in the economic argument against SB-237 is that it ignores the enormous waste of teachers’ time trying to teach reading to students who are neurologically not able to respond to conventional instruction. Student time is wasted, as well. How many tens of millions of dollars a year is utterly lost annually, just in the early elementary grades? My estimate is $350 million. Read on to see how I arrive at that figure.

About 1.4 million students were enrolled in K, 1 and 2 in the 2019-20 year, before the pandemic. Take 15 percent of them as likely to be dyslexic: 210,000. Take the proportion of the school year dedicated to the teaching of reading in those grade levels (55 percent). Round that to 50 percent for this back-of-the-napkin exercise. Apply that to a 180-day school year. The result:

- About 4,600 teachers wasted their time for a year, based on average class size of 22.8 in the 2018-19 year, the most current year for which CDE has published staffing data (or 828,000 teacher days wasted);

- About $350 million dollars wasted paying them for ineffective instruction, at an average annual salary of $76,000;

- About 18,900,000 days of frustration-filled effort spent by dyslexic students trying to read when their brain wiring renders them unable to respond to conventional instruction.

A full accounting for the cost of not screening would go much farther, and include the cost of sending some portion of those 210,000 students into the world not able to read. But I’m not going to run with this. I’d rather leave you with the simpler, one-year cost of one thing only: wasted instructional time. If you’re a district administrator, you may be working on budgeting now. If you’re wondering how to make ends meet, try factoring in this single waste factor and see if that offsets your projected shortfall.

What you can do about it

Do you think California districts could pay for a dyslexia screening battery with the $350 million wasted each year? I don’t know the answer. But halting this extraordinary waste would be a step in the right direction.

If you are an administrator, write or call Mark Ecker (interim exec director) and Dr. Edgar Zazueta (incoming exec director as of June 1) at ACSA and tell him why ACSA should support this bill’s passage. (ACSA had no position on SB-237.) If you’re a school board trustee, write or call Vernon Billy at CSBA and do the same. If you’re a parent, write or call Carol Green (president) or Shereen Walter (president-elect), or Sherry Skelly Griffith (executive director) of the PTA. If you’re a teacher, write or call Joe Boyd, CTA’s executive director. If you’re a citizen, write your state senator and tell her or him to support SB-237.

California has every reason to join the other 39 states in making dyslexia screening mandatory. Let’s get that bill turned into law.

- Luz Rullo, Kristin Williams, Abdullah Ali, Nancy Cushen White, Jeffrey P. Bingham, “Dytective: Towards Detecting Dyslexia Across Languages Using an Online Game,” April 2016, Proceedings of the Conference of the 13th Web-for-All association. Article #29. Pages 1-4.

- Luz Rello, Ricardo Baeza-Yates, Abdullah Ali, Jeffrey P. Bigham, Miquel Serra, “Predicting risk of dyslexia with an online gamified test,” December 2020, Public Library of Science, PLoS ONE 15(12): e0241687.