What is the implied promise in the contract between school districts and the parents who bring them their children to educate? The first promise is that their children will learn how to read. In some districts, that may come to pass. But in too many districts, only 6 or 7 or 8 out of every 10 students learns to read.

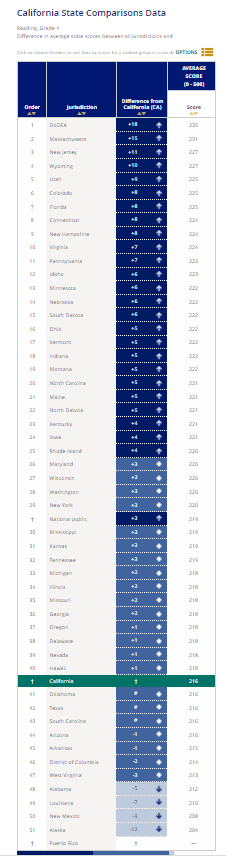

NAEP test results showing state-by-state ranking of 4th graders’ reading results on the 2019 test cycle. California (highlighted in green) ranks 41st. (Source: National Center for Education Statistics)

Here’s the big picture. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) of 2019 reveals how California’s 4th graders are doing at reading, compared to their peers in other states. On the whole, California is 41st in this ranking, and that’s the best year for 4th grade reading scores since 1992. Since California leads the nation in poverty, let’s look at those kids who were eligible for subsidized meals. They ranked 38th. For those not eligible, they ranked 15th.

But between 7 to 15 percent of all people are dyslexic, which is to say they have a neurological problem connecting the shapes of letters with their sounds. Combining letters into syllables, and then into words and sounding them out, is how most of us learned to read. But it is unusually challenging for dyslexic kids to do this. The good news is that they can learn to read if they are taught in a way that matches their strengths and avoids their weaknesses. Modern minded school districts know how to identify students who are likely to be dyslexic, and also know how to teach them to read. Indeed, all students can learn to read, but not all district leaders know how to make that happen.

There is more good news. The advances of psycholinguists and neuroscientists in the last five years have made it easier to identify which kids are dyslexic. To capitalize on these breakthroughs, 35 states have passed laws that require school districts to screen all students for signs of dyslexia. Unfortunately, California is not one of them. California, our not-so-golden state, has taken only a half-step in the right direction.

In 2017, the CDE issued dyslexia guidelines, and issued them as recommendations. The CDE editors or authors declared at the beginning of the 130-page document that the guidelines were not mandatory. This is the exact language, and it appeared prominently opposite the table of contents: “The guidance in California Dyslexia Guidelines is not binding on local educational agencies or other entities. Except for the statutes, regulations, and court decisions that are referenced herein, the document is exemplary, and compliance with it is not mandatory.” (Of course, if they were mandatory, then the cost of following the guidelines would be reimbursable. The Dept. of Finance would never stand for that.)

The guidelines are great, but their voluntary nature is just another sign of California’s backwardness. However, Gov. Newsom has done much to lead California out of its know-nothing legacy, and into the era of enlightenment. In addition, state senator Anthony J. Portantino (D – La Cañada-Flintridge) has authored a bill (SB-237) that would require dyslexia screening. This excellent op-ed in the LA Times by Bill Lucia of EdVoice championed the bill. It made it through the Senate education committee, but the Assembly Education Committee refused to act on it. So it is dead for this legislative session.

Why dyslexia screening is a litmus test

Here’s why dyslexia screening is a litmus test of a district’s commitment to teaching reading. If a district in 2021 is not screening for dyslexia, they are declaring their disinterest in teaching reading to 1 out of every 10 kids. By deciding to not screen, and not follow the California dyslexia guidelines, they are signaling their disinterest in helping students with the most prevalent learning disability. It is an abandonment of the educational mission, a breach of contract to teach every kid to read. (No, I am not a lawyer. But I admire the public interest lawyers who have fought for and won students’ constitutional right to learn to read.)

I have a hunch that these non-screening districts are likely to have blind spots in other areas that require solid evidence and sound judgment. I would like to find out if these districts are not measuring:

- the fundamental phonics skills or the oral fluency of emerging readers;

- the readiness of their entering kindergartners for school (do they know their numbers, letters, colors, etc.);

- the rate at which each of their schools is referring students for Tier 2 reading supports;

- the timeliness of their referrals to Tier 2 (were referrals made at the earliest possible moment that a student was identified as needing help);

- the frequency of errors in judgment in making those referrals – identifying kids for help who don’t really need it, or failing to identify those kids who really do need help.

California’s blind spot to dyslexia screening

But I can’t find out if my hunch is true, because the CDE doesn’t know which districts have followed the dyslexia guidelines and started screening students for signs of dyslexia. No legislation required that they do so, it’s true. So no one in that big building has shouldered the job of surveying the field. Why aren’t county offices of education rushing to fill this vacuum? Why isn’t ACSA or CSBA doing something to survey their members? With $37.5 million in early literacy grant funds just awarded, I can only hope that one of the grant recipients finds the time to fill this knowledge void.

Dyslexia screeners vary in quality and cost

Screening for dyslexia is feasible at relatively low cost. But screeners are varied in their quality, their approach, their sensitivity to identifying truly dyslexic kids, and their specific ability to not incorrectly overidentify too many kids. Some are well suited for kids who don’t speak English, and others are not. Some screeners can be given to a student in 15 minutes. Some screeners require that teachers give it to a kid one-on-one. Others provide for students to take a test on a computer. Some screeners start with pre-K students, but others with kindergartners. Some screeners are age-level and grade-level appropriate. Others are not. Some screeners are discrete assessments, built solely for the single purpose of correctly identifying likely dyslexics. Other dyslexia screeners are one part of broader early literacy tests, designed to assess emerging phonics skills, oral fluency or more. Many of the big testing firms are now making claims that their early literacy tests can be used for dyslexia screening. Only some provide evidence that supports that claim, and I’ve found none whose claims of dyslexia screening viability are supported by third-party research.

I’ve just completed a national review of dyslexia screeners on behalf of a client district, and I can tell you that it’s a wild west show out there. I will soon share some of my findings in a follow-up blog post on the market for dyslexia screeners. I am excited to have learned about the work of the UCSF Dyslexia Center to develop a well-rounded battery of assessments and family history, in a joint effort with scientists at Stanford, UCLA and UC Berkeley. In the meantime, here is a link to their Dyslexia Phenotype Project which shows the range of approaches they are combining as they build practical solutions. And here, too, is a link to the APPRISE screener they developed in conjunction with scientists at the University of Connecticut.

Good news: districts are free to do the right thing (without being told)

The best part of this era of local control is that districts don’t have to wait to be told to do something. They can just go ahead and do it. District leaders don’t need to wait for California’s legislature. They can simply do what 35 states are already doing, and start screening for dyslexia.

Also to come … news of the CDE’s award of Early Literacy Grants that include some attention to dyslexia. Stay tuned.