How quickly our words get away from us. We sometimes sow the seeds of misunderstandings when we use words that don’t really mean what we think they mean. In a field as jargon-filled as education, perhaps we should slow down and choose our words more carefully.

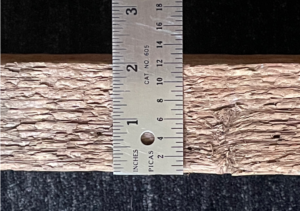

Consider the term “2×4.” This is a familiar phrase to carpenters. It describes the basic piece of lumber used to frame houses. But that term is outdated in two ways. First, a 2×4 hasn’t measured 2” x 4” for decades. It measures 1.5” x 3.5.” Second, the cost of lumber has led many home builders to rely on metal 2x4s instead of wood.

Misnomer example #1: the English learner student label

This is a true 2×4 salvaged from an old building. New 2x4s measure 1.5″ x 3.5.”

Why do we call kids English learners when many speak playground English about as well as their English-only pals, and read and write about as well as them, too? Educators hang that label on a student if two conditions are met: (1) their parent checked a box on a form indicating someone at home speaks a language other than English, and (2) the student scored below a threshold score on a test of English fluency (the ELPAC in California, successor to the CELDT).

Give that same English fluency test to other kids from English-only parents, and you may discover that many of them would qualify for labeling as English-learners. (See study by Katie Stokes-Guinan and Claude Goldberg, “Use with Caution: What CELDT Results Can and Cannot Tell You,” 2011.)

My question: why don’t we call this kid an emerging bilingual student? The label begins with an attribute of the family’s spoken languages, not the child’s, after all. If the student has some command of the family’s other language, and she is acquiring English language skills as well, doesn’t that put her on the road to bilingual capability?

Misnomer example #2: ethnicity and race labels

Hispanic/Latino is a category we are supposed to consider to be a “race.” Its counterpart: non-Hispanic/Latino. This category schema was the result of much debate, and finally formalized about fifty years ago by federal law, and was then adopted by the Census Bureau. (You may consult this Wikipedia entry if you wish to dive in and learn more.) But many people who claim to be descended from this “race” are often neither Hispanic nor Latino. Many are indios, indigenous people of the Americas. They may have no ancestors from Spain or Hispaniola.

Those two “races” are supposed to be different in nature than “ethnic” categories: White, Black, Asian, etc. We toss these around like they have a shared meaning, one we can all agree upon. Our use of the terms, because they’re in use everywhere, seems to be normal. But it is not. “White” does not describe my skin color or ethnicity any more than “Black” describes the ethnicity or skin color of my friends whose ancestors came from Cuba or Brazil or Liberia. The common term of an earlier era was “Negro.” That term superseded “colored people.” We now hear the term “people of color.” Are we coming full circle?

But more importantly, why do we use words whose meaning is so vague? Why do we use words that name colors to describe people whose ancestries vary so greatly? Isn’t this similar to the holdover of the term “2×4?” It didn’t used to be this way. Louisiana before 1803 was governed by the French and prior to that, the Spanish. They had discrete terms for mixed race people: octoroon, quadroon, and so on. Free people of color also were well established, especially in New Orleans. In that place at that time, skin color did not imply race, but ancestry. And words described ancestry more accurately than our words do now.

Loose use of words points to loose thinking

And if those categories are so mixed up and ill-defined, why do we continue to examine differences in educational outcomes based upon that attribute alone? We may be pursuing a moral purpose, justice for all, and a fair sharing of resources. But if we reduce all variables to race or ethnicity, and ignore the rest, we are likely to fail in our pursuit of a higher end.

My suggestion … let’s be more deliberate before throwing these terms around. Let’s consider the multi-causal nature of most outcomes in life. Let’s stop and think … and then speak after choosing our words with greater care.