I have a hunch that you may not be looking forward to starting your district’s new three-year LCAP. You’re up to your eyeballs with short-term planning for getting instruction delivered. Who’s teaching remotely? Who’s teaching in classrooms? How is remote assessment working? Who’s the best teacher in our elementary team at delivering instruction via Zoom? It makes three-year planning seem impossible. You sigh and think, “Sure, we plan. Then life happens, and we forget the plan.”

The gravitational pull of the status quo is the elephant in the room. The pandemic can help you reach escape velocity.

But think again. When the normal rhythms of schooling are disrupted, isn’t it an ideal moment for rethinking how you educate students?

Why write a three-year plan that just maps out a return to normal? Was the status quo really working well for all students? If not, why don’t you clear the decks, push your prior plan aside, and start fresh? The elephant in the room is not the pandemic. It is the gravitational pull of the status quo.

What Does “Start Fresh” Mean?

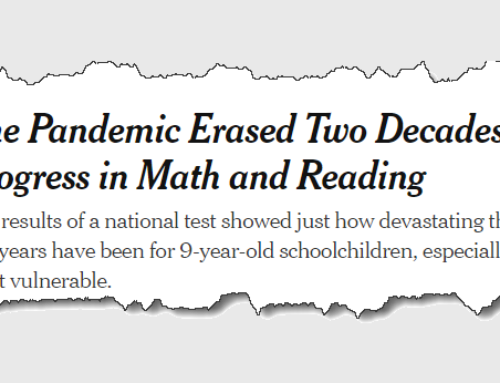

“Fresh” could mean you set your sights on fundamentals, like assuring that 90 percent of your students reach grade-level reading skill by end of third grade. (That’s what the experts say is possible.)

“Fresh” could mean you set your district’s goals, framed not by norms, but on comparisons of how schools or districts with highly similar kids are doing.

“Fresh” could mean that you take more seriously the reclassification of students learning English, and set grade-level targets that will assure no student becomes a long-term English learner.

“Fresh” could mean getting your counseling team staffed at a ratio that’s a reasonable case load instead of the 566-to-1 ratio we saw in California for the 2018-19 school year. (“Reasonable” for the American Counselor Association is 250-to-1.)

“Fresh” could mean facing the evidence you hear from students, parents and teachers about weak writing instruction. Perhaps this is the LCAP that will recreate the success of a prior decade in writing across the curriculum.

The opportunity a pandemic brings is to break from the habit of status-quo planning. Stop aiming to recreate what you did last year. I’ve seen many dozens of LCAPs, and far too many just rationalized the decisions leadership made in the past: adopting questionable curriculum, hiring questionable staff, continuing questionable programs. Now is the time to look at the evidence of past practices, and ask questions:

- To what extent did these work, and for whom?

- To what extent did they not work, and for whom?

- What was the cost of those results, both successes and defeats?

Who Should Be On Your LCAP Team?

Build sound evidence and summon the spirit of inquiry. Build your LCAP team differently this year so it includes a hawk-eyed detective, a forensic analyst, a devil’s advocate, and a frugal economist.

The detective looks for signs of failure, friction and frustration. They are masters of evidence. Detectives are watchdogs of waste. Time and money are wasted in every organization. Why not find a detective for your LCAP team who hunts for waste like a bloodhound.

The forensic analyst gathers evidence and tests it in the lab. She commands many modes of analysis. Her tools aren’t limited to spreadsheets. She’s not enamored of measures of averages. She wants to see all data points. She loves to poke at outliers. She’s a stat-head, a data viz geek. She seeks correlations but doesn’t rush to discover causal contributors too quickly.

The devil’s advocate keeps your team from reaching conclusions too quickly. You need someone who imagines a dozen reasons why a pattern of lagging readers emerges in first grade. Your devil’s advocate challenges every hunch. He annoys everyone with his nay-saying and his doubts. Consider him to be your quality-control person who keeps hunches from becoming assertions without being heavily tested.

The economist figures out the cost of every benefit. Your LCAP will have to put dollar to solutions. Are those solutions creating benefits of the right type at the right price? Are there other solutions that produce a similar effect at a lower cost? Economic thinking about cost-utility, cost-benefit, and cost-efficiency is almost always lacking in LCAPs. This is not budget-centered thinking, either. You need an economist, not a finance person from the business office.

And if you have LCAP team members who want to blow it off, and are cynical about the reason for planning, tell them they’re off your team. Free to go. You need no slackers for this LCAP cycle ahead. You need no “yes” men. You need thinkers. You need people who share your view of the opportunity. Start searching for them now. They’re out there, if not within your district office, among your principals or senior teachers. You will find them.