Supt. Barbara Nemko has taken steps to help Napa County districts plan smarter.

Barbara Nemko, Napa CoE’s superintendent, wants districts’ plans to get smarter, and she’s ready to shoulder more responsibility for making that happen. Already she’s invested in better evidence for planning, and in analytic support and coaching for her LCAP chief. And she’s welcomed district leaders to work with her team as thought partners.

But Supt. Nemko also welcomes a change in the rules and regs that now limit CoEs to a pro-forma review. Here’s what she favors (sent via email) when I asked her for her views:

“Right now, CoE’s are only permitted to do a once-over-lightly about compliance with the requirements of the LCAP, but no deep dive into the content or results…. With billions of dollars allocated through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) requiring school districts to write a Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP), explaining how they will spend the money to improve educational outcomes for the most at-risk students, isn’t it time to put some serious oversight into how the money is being spent? And what results are being achieved? County Offices of Education have teeth when it comes to budget oversight, thanks to AB 1200. Why not give them the same oversight on the education side of the house?”

Her ideas are consistent with a report from the Legislative Analyst’s Office of January 2020. They urged that the Legislature “… would direct CDE, CCEE, and the COE geographic leads to develop a set of LCAP review standards…” The LAO’s report explains what the next step might include. “Based upon a holistic review of the district using the new review standards, a COE could assign a qualitative rating to the LCAP—for example, positive, qualified or negative (borrowing terms COEs already use to review district budgets). A poor LCAP rating would trigger more COE support for the district. Such an approach would make COEs’ role in instructional oversight somewhat more analogous to their role in fiscal oversight.”

You can read more about the LAO’s smart suggestions for putting some real substance into the LCAP review process by turning to this blog post I wrote last March (6 minute reading time).

Inaction on all fronts

Supt. Nemko and the LAO are not alone. In private, many superintendents of both districts and CoEs have expressed exasperation about the LCAP. In a study by Julia Koppich and Daniel Humphrey in September 2018, part of the “Getting Down to Facts II” series, was based on interviews with over 80 superintendents. (See this blog post for a recap of that report.) Koppich and Humphrey saw a pattern of criticism centered on compliance thinking, excessive complexity, and unreadability.

Given how compelling their report’s evidence was, I expected to see the organizations that represent leadership challenge the CDE’s bureaucratic regs, and champion reform legislation. But no sign of action is visible. Not by CCSESA. Not by CSBA. Not even ACSA, to the best of my knowledge, has registered a single complaint about the ease with which vacuous LCAPs win approval from CoEs and school boards. So district planning teams have no reason to do anything other than repeat what they’ve done in prior years.

The repetition of the LCAP charade

No one really enjoys playing the LCAP charade. Yet no one stops playing. Everyone continues to repeat their prior error-filled steps.

- Step 1: Dust off last year’s plan;

- Step 2: Look at the most recent Dashboard color grid, and see where your district looks good (blue or green) or bad (orange or red);

- Step 3: Modify your prior plan, admit that your district regrets missing your prior LCAP’s goals, express your dismay at anything that’s orange or red, and then promise to do better next time;

- Step 4: Affirm again the remedies that you affirmed last year, that the path to improvement is to spend money on staff development and new programs;

- Step 5: Present the plan to staff and the public;

- Step 6: Present the plan to the county office for review, and then to your board for approval.

Can we just get real here, and admit this is not working? The plans that are filled with flawed evidence and riddled with illogic, and projections of improvement that are based on faith and magical thinking keep getting approved. If you’re not convinced it’s really this bad, allow me five minutes to show what’s wrong with each step.

Step 1. Dusting off last year’s plan is simply a way to plan to repeat what you did last year. It avoids the hard part: thinking, evaluating, identifying failures. Everyone whose program was funded, and every staff person in place, might appreciate a status-quo plan. But that’s not what planning is for.

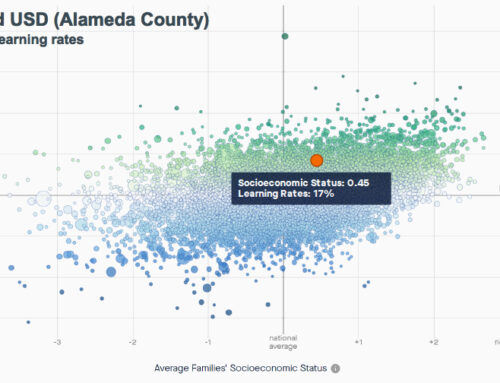

Step 2: The CDE’s Dashboard is full of broken gauges. It is often wrong, conveying errors baked into colors that do not mean what you think they mean. Those errors are due to flawed logic and arithmetic mistakes, and if you want to learn more about the range of problems with the Dashboard, you can read this essay in Ed-100 I wrote last June. If you want to dive in more deeply, here’s a link to the many blog posts I’ve written about the Dashboard’s flaws. The good news is that the evidence planners need is already in their hands. But rarely do they source that higher quality evidence. (Let me confess to self-interest here. I lead the K12 Measures team, which for the past four years has built high quality, comparative evidence for LCAP and SPSA planners.)

Step 3: Admit to mistakes or underperformance. All districts have a ritual moment in their LCAPs when they are expected to hang their heads in shame, and confess to their sins. It’s all based on what the Dashboard tells them is wrong. And the Dashboard’s conclusions are almost always incorrect. So this ritual of confession is just pro-forma. It means nothing. I’ve read dozens of plans, and have looked in all of them for earnest, authentic admissions of errors in judgment, large or small. I’ve never seen a plan that admitted to teaching reading the wrong way, or selecting the wrong middle school math curriculum, or failing to advance quickly enough the English fluency of students who are emerging bilingual students, and thereby creating long-term English learners.

Step 4: Whatever the problem, the remedy can’t always be the same — either staff development or a new program. I’m amazed at the consistency of the treatments that plan authors call for. Can life really be that simple? It reminds me of the medicine show con-men in the Wild West, who’d pull into small towns selling Dr. McAfee’s Lizard Juice Elixir as the cure for headaches, rheumatism, arthritis and the common cold.

Step 5: Then districts circulate their 180-page LCAPs to the public, and distill it into an hour-long, 60-slide presentation. If it goes well, most people have either fallen asleep or left. If it goes badly, those who are still awake throw questions at the presenter who deflects with shields made of education jargon. I think my college term papers got closer scrutiny than the plans that determine where districts’ hundreds of millions of dollars go. Considering that about 40 percent of the California budget goes to K-12, all of it justified in LCAPs that never pass an external qualitative review, perhaps the cost of this sloppiness warrants attention.

Step 6: The final step is the charade of the county office’s review. The county team in charge of reviewing and approving these plans is handcuffed by policies that don’t allow for a review of a plan’s evidence, its identification of priorities, its reasoning or its conclusions. If a district presented an LCAP that said they were going to improve their graduation rate by recruiting tutors from San Quentin prison, a county office wouldn’t be able to reject the plan. Only that district’s board would have the authority to send it back for rethinking. (By the way, if you know of any board that ever rejected the LCAP their team brought them, please email me pronto.)

Actions you can take now

This last step is an opportunity county office leaders can grasp with their two hands. Just question flawed evidence and illogical thinking. When you spot these flaws in districts’ plans, just circle them in red, and explain their reasons for doing so. Then tell the LCAP’s authors that their plans need work, and send them back for revision. District LCAP teams can either heed or disregard this due-diligence, under the current rules of the game. But nothing prevents CoE LCAP reviewers from taking this step.

For those of you who are county office superintendents or leaders of county office LCAP review teams, take a hint from the LAO’s report. If you really want to end the charade of reviewing LCAPs, then start acting as a thought partner with your districts. Napa CoE’s director of continuous improvement, Lucy Edwards, has done just that. She invited district LCAP leaders to share their thinking, before they drafted their plans. Her diplomacy has enabled her to build a climate of trust among their five districts and with her, that makes year-round collaboration possible.

You might prefer to create a peer review process, guided by standards of evidence and logical reasoning that you define. (Academic journals use this system of critique for improving the quality of articles submitted.) Not all districts will say yes to your invitation. But if even some of them accept, wouldn’t that be progress?

And for those of you who are district superintendents or LCAP team members or leaders, aren’t you ready to welcome this help? Aren’t you tired of the same-old ritual of pretending to plan? Aren’t you exhausted by year after year of inventing progress targets and failing to meet them? If you want technical support to measure the right things the right way, isn’t it time to ask for help?