I am troubled by signs of growing opposition to testing. One indicator is the popularity of the book by Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan, Street Data (Corwin, 2021). The book has been ranked on Amazon as either the #1 or #2 seller in the category of education administration for months. In Amazon’s larger category of education books, at the end of September, Street Data ranks #10, well ahead of John Hattie’s new book, Visible Learning: The Sequel, which is ranked #19, and Robert Marzano’s book, The New Art and Science of Teaching, ranked #21. In my eyes, the popularity of Street Data spells trouble.

I am troubled by signs of growing opposition to testing. One indicator is the popularity of the book by Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan, Street Data (Corwin, 2021). The book has been ranked on Amazon as either the #1 or #2 seller in the category of education administration for months. In Amazon’s larger category of education books, at the end of September, Street Data ranks #10, well ahead of John Hattie’s new book, Visible Learning: The Sequel, which is ranked #19, and Robert Marzano’s book, The New Art and Science of Teaching, ranked #21. In my eyes, the popularity of Street Data spells trouble.

(A declaration of professional envy is in order here. I have written a book – Mismeasuring Schools’ Vital Signs (Routledge, 2022) — and wish it were selling half as well as Street Data.)

Friends in several districts have told me the book has even been the focus of professional development sessions. Gushing praise is evident on Shane Safir’s website. This is not a topic that usually prompts emotional standing ovations. What’s happening here?

When self-proclaimed “equity warriors” take on empiricism and measurement, watch out.

These rankings are indicative of a change, I sense, among both admins and teachers, who are increasingly vocal in opposing the instrument by which schools and districts are compared. It isn’t just the tests themselves that are the object of Safir and Dugan’s wrath. After reading its pages with care, I assure you they are after much bigger fish. They are opposed to empiricism itself and its methods: observation, recording observations with measures, evaluating those observations, constructing a hypothesis, and testing that hypothesis against one’s findings.

Safir and Dugan juxtapose empiricism to “… innate ideas or traditions.” What are “innate ideas” anyway? Do the authors really think we are born with them?

The authors believe empirical methods are instruments of “white supremacy.” And wrapping themselves in the magical mantle of “diversity warriors,” they urge educators to become amateur anthropologists, studying the tribe called “students,” and gathering artifacts of students’ ideas, attitudes and behaviors. I don’t believe ethnographic research is a faith-based initiative. It’s a discipline in the social sciences. And calling yourself a “diversity warrior” does not invoke a Star Wars power shield that will protect you from criticism.

The authors then call empiricism a “Western approach to knowledge,” and then call it “white research” and “outsider research,” invoking the writing of Stuart Hall. (An aside here … I know Stuart Hall’s work. He is a scholar of the left, a co-founder of New Left Review, and a rigorous intellectual who I suspect would laugh at discovering he’s being used to champion an attack on “Western approaches to knowledge.”)

Is opposition to testing surging only in response to NCLB’s misuse of measurement?

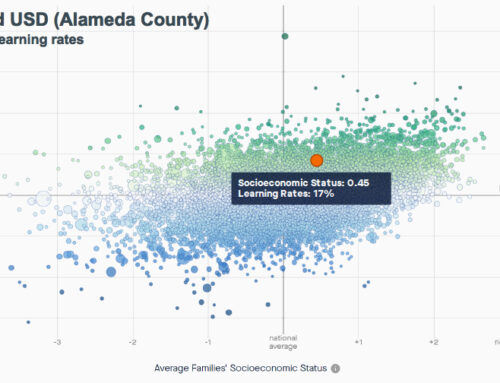

But I also believe the authors oppose testing because it is the bridge to the broader public’s knowledge of how schools are doing at enabling students to learn. Shafir and Dugan don’t mention the public’s right to see a measure of results. One Minnesota parent (@CitizenStewart) created this Tik Tok video to explain in about nine minutes why he favors end-of-year testing. He makes a case for the benefit that standardized tests bring him as a parent. He’s not without empathy for teachers. But he critiques the National Education Association (NEA) for their opposition to testing. The other teachers union, the AFT, defends testing. And he praises the civil rights organizations for defending testing.

I have a hunch that it is the combined effect of the decline of the accountability era, and the failure of the measurement movement, that has led to this state of affairs. Telling teachers to “just use data” was a poor message. Using standardized testing data crudely to infer the quality of instruction was a mistake (and thanks to Jim Popham for trumpeting this message far and wide). Comparing schools based on how the tested grade levels scored in consecutive years was a dumb move. Looking at the effect of school on kids can be done by looking at graduating class cohorts over time, or even better, the same kids continuously enrolled over at least several years. And handing out money to principals and teachers as a reward for high test scores was an invitation for trouble.

The tests were designed to reveal schoolwide and districtwide whether students were on grade level for a sampling of the standards tested. When tests were proposed to be used in Tennessee to evaluate teachers, using a value-added approach designed by Bill Sanders, the intensity of the voices of the opposition chorus rose considerably.

The NCLB era led to the association of standardized tests with punishment. Mistaken uses of test data were baked into legislation. Aspirational goals (all students proficient by …) led to an aspirational measure called Adequate Yearly Progress. And no surprise, “test” became a four-letter word. Since most administrators had little to no assessment education in their pre-service years (see Mandinach and Gummer’s book, Data Literacy for Educators, 2016), and since admin credential programs in most states don’t foster assessment or data literacy, they have little knowledge to draw on when it’s time to respond to the challenge.

It is this series of errors that has provoked this strong blow-back. And now the opponents have an “equity warrior” in the form of Shane Safir who has renounced empiricism, and is ready to minimize the place of evidence in schools. She is ready to bond with students and oppose those who would tell them how to teach or what to teach, based on evidence of learning that can be expressed in numbers. In Shane Safir’s world, “street data” is simply written documentation of students’ views, attitudes and behaviors. There is no counting of anything in the world of “street data.” There are only words, and the closer to the “street” those words are, the more value she gives them.

More debate is needed

Stay tuned. Street Data deserves a full review of its own. (I’m working on it, and hope that others are, too.) The issues Shane Safir and Kamila Dugan raise are important. I also agree with some of their assertions. Their critique of the achievement gap’s excessive attention-drawing power is interesting. I applaud their attention to the damaging effect on students when they hear teachers say that their skin color or country-of-origin may be a barrier to learning. Their views about the value of listening to students’ views are worthy. But their arguments go well beyond this, and deserve a challenge, not gushing adoration.