Each November, I go to the annual conference of the California Education Research Association hoping that it will take a stronger leadership role, more independent of the CDE, and more ahead of its members. But again this year, my hopes for the organization were not met. And this was a year when leadership was sorely needed.

In a moment when a new data system to replace CALPADS is in its formative stage, when the Dashboard has been abandoned by districts that account for one-third of the state’s enrollment, and when remarkable discoveries are coming from the research team running Stanford’s Education Opportunity Project, I expected debate and dialogue. Instead, I encountered a slew of workshops that offered unending praise for the Dashboard, no critique of bad use of test results, no mention of the new legislation that funds planning for a new student longitudinal data system, and no debate over a state policy that still has not defined what “growth” means.

(By the way, only two states still lack a growth measure: our state and Kansas.)

This is not the sign of a healthy organization. Healthy organizations create an intellectual climate where many points-of-view can be heard. Healthy organizations welcome debate. Healthy organizations have a vocal membership, and two-way communication between members and leadership. Healthy organizations enable conversations among members. Healthy organizations have publications that share knowledge and opinions. (Yes, I know CERA runs lean, and is staffed only by volunteers. But none of the signs of health I’m pointing to require a lot of money or time.)

The American Education Research Association (AERA) shows all these signs of health … and more. Debate and dialogue are evident in its journals and at its annual conference. So the problem isn’t a curse that afflicts all education research groups. It just afflicts our own. (Why in 2.5 days at CERA did I not see or hear a single reference to AERA’s annual conference set for mid-April 2020?)

I offer three observations of CERA’s ailments. I do so in the hopes this starts a conversation.

#1: Education research leaders weren’t at the conference.

I know from having attended CERA most of the past 20 years, that it is a practitioner dominated organization. But in a state where extraordinary education researchers are hard at work, why aren’t they invited to present? Just two examples come to mind: Sean Reardon from the Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis and the Stanford Education Data Archive; and Paul Warren from Public Policy Institute of California.

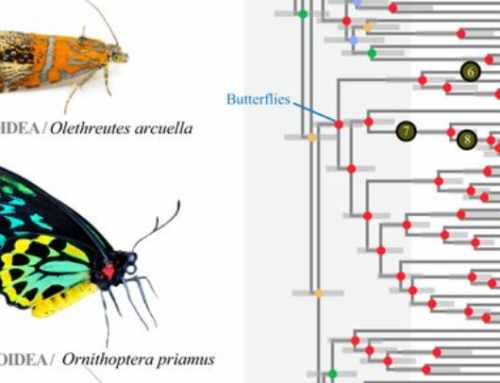

Sean Reardon and his talented team have done remarkable work in the study of education inequality, that has yielded not only a small mountain of published research, but which has also resulted in a research asset of 300 million student records available to others. His work has, in the last four years, resulted in at least four article in the NY TIMES that I could find, including “Money, Race and Success: How Your School District Compares,” and “How Effective Is Your School District? A New Measure Shows Where Students Learn the Most.” The most recent off-spring of Reardon’s creative work is the Educational Opportunity Project.

Paul Warren has been a researcher with the Public Policy Institute of California since May 2012. His writing about education policy is well-informed by his four years (1999-2003) as Deputy Chief SPI at the CDE in charge of testing and accountability. His report of July 2019 interprets the most recent CAASPP results. His seven blog posts in the last 12 months includes this one about the threat to many districts of enrollment decline. And a topic highly relevant to the CERA conference attendees was his June 2018 report that criticized the Dashboard’s flaws, especially its misinterpretations of growth in students’ CAASPP results.

With Paul Warren’s offices located a five-minute walk from the Sacramento convention hotel, and with Sean Reardon’s team based at Stanford, it would have been easy for both to attend. Their messages need to be heard by CERA members.

#2: No acknowledgement that the Dashboard has been left behind by enough districts and counties to account for one-third of California enrollment.

Could it be because the Dashboard produces as much “noise” as “signal?” Could it be tagging the wrong districts as needing improvement, and fails to tag the right districts? While researchers like Paul Warren and scholars like Morgan Polikoff (USC Rossier School of Education) have criticized the Dashboard, many district leaders have simply chosen not to use the Dashboard’s findings for planning purposes. These quiet refuseniks are the CORE Data Collaborative members. Noah Bookman, who leads the CORE Data Collaborative, told me that 125 districts and 9 county offices of education have joined – and as a result have a different base of evidence of how they are doing, based on student level records. Together they account for 2 million students, about one-third of California’s entire K-12 enrollment.

Why weren’t the CORE leaders invited to present their models of growth, methods and stories of applied measures to planning? They’ve been invited to prior CERA conferences. They have earned a place at this conference for their alternative views, which should be visible every year.

#3: Not one workshop on the bill (SB2-Glazer and Allen) that would fund planning for a new student longitudinal data system that may retire CALPADS and join K-12 data to pre-K and college data.

This holds great promise, and could mark the end of a dark era for state data stewardship. Gov. Brown set back California a decade by disbanding CPEC, defunding CalTIDES (the teacher database), and failing to weave matrix questions into the CAASPP to make its results roughly relatable to CST results. Is no one excited by the opportunity to build a P-20 database that would build evidence for answering a host of “big picture” questions? Isn’t this exactly the sort of bill that CERA’s board should bring to its members’ attention?

The opportunity. I still believe that CERA holds great promise. It could provide much needed cross-pollination across the practitioner-researcher divide. It could challenge schools of education that are sending teachers and administrators into the field poorly prepared to interpret assessments. It could advance the continuing education of its own members. With a state board and state education agency blocking the road to smarter measurement, it’s time for CERA to break from its all-too-cozy relation to officialdom and lead its members to a higher level of measurement professionalism.