At this year’s annual American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference, education scholars presented 2,188 papers, symposia and roundtables–all of it online, of course. I was happy to “attend” without the cost of travel. But I was especially eager to scout new findings on two topics–dyslexia and identification of English learners–relevant to districts in California my firm serves as analytic partner (we help district and site leaders find better evidence, and make better sense of it.

[Note: This essay appeared in Education Week on May 6, 2021, as a guest commentary within Rick Hess’s column, “Straight Up.”]

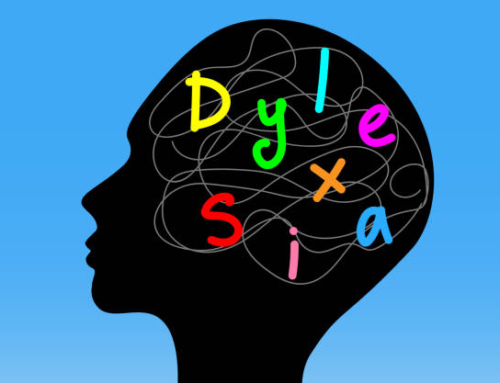

Happily, I was able to search the text of all presentations, independent of tags and keywords. Kudos to AERA for this. With high hopes, I typed “d-y-s-l-e-x-i-a.” Six instances of the term appeared. I thought that I’d perhaps misspelled the word. I tried again. Six results. Of all the learning disabilities, dyslexia ranks highest. According to the International Dyslexia Association, as many as 15 to 20 percent of Americans may be dyslexic. How could ed researchers pay it so little attention?

Happily, I was able to search the text of all presentations, independent of tags and keywords. Kudos to AERA for this. With high hopes, I typed “d-y-s-l-e-x-i-a.” Six instances of the term appeared. I thought that I’d perhaps misspelled the word. I tried again. Six results. Of all the learning disabilities, dyslexia ranks highest. According to the International Dyslexia Association, as many as 15 to 20 percent of Americans may be dyslexic. How could ed researchers pay it so little attention?

Next, I tried two terms that are at the center of the stormy debate about how to teach reading: Balanced Literacy and Structured Literacy. They are proper nouns. They describe two different approaches to teaching reading. The pages of Education Week have dedicated many column inches to this debate. But the scholars presenting at the AERA conference are apparently not interested. I discovered a grand total of one mention of either of those two terms.

I soldiered onto my next topic: identification of English learners. I was happy to discover a fair number of presentations (124) that fit my clients’ interests. In the past, I have found practical, actionable research by Peggy Estrada (UC Santa Cruz) on long-term English learners, so this term was at the top of my list of things to search. But total references in this year’s AERA conference to the term “long-term English learner” numbered just 24.

What I couldn’t help but notice at this AERA conference was the amount of attention to race and ethnicity. So I queried a few terms. Here’s what I found:

equity …………….… 507 results

gap ………………….. 380 results

intersectionality .. 372 results

whiteness …………. 466 results

In light of the news of the last year, I understand why these dimensions of education are front and center now. I understand and favor a forceful, visible and moral dimension to research. But what I don’t understand is the shortage of attention to subjects like dyslexia, the teaching of reading and identification of second language learners. Just consider the weight of “whiteness” to “dyslexia” (78-to-1) or to “long-term English learners” (19-to-1). It is a striking imbalance.

“Whiteness” may be an important and relevant topic for a conference of political scientists, anthropologists, or sociologists. But why is it so forward in the scholarship of education researchers? I suspect it is a sign that many of those who produce education research are producing work for other scholars. Too many are self-sequestered in universities, separate from the larger world of K-12 schooling. This leaves them inattentive to the practical research needs of educators and those who manage them.

As a broker of research to those education leaders, I feel the pain of the district people we work for. They need clear-headed evaluation of curricula. They need to know the imprecision of the assessments they use. They need to know why the teaching of foreign languages to so many high school students goes to waste. They need to know where their dollars produce the best return-on-investment. These are practical questions, not political ones.

One example I can share of practical research, applied to a client district’s problem, shows why I value actionable research so highly, and am disheartened by those who invest their time elsewhere. In our work with clients in California, we have seen districts differ greatly in their pace and approach bringing emerging bilingual students (English learners or ELs) to fluency in English. In California, even districts whose students are highly similar can take as few as four years to reclassify these students, while others will take almost seven. Since districts in California function as islands, they are often unaware of the degree to which they are leading or lagging.

The research of Peggy Estrada (University of California, Santa Cruz) on the ways that district rules create long-term English learners proved to be enlightening for a client in Napa county, where more than 40 percent of the students are identified as ELs. Estrada and Wang’s research comparing two districts’ approaches to determining when students should be reclassified as fully English proficient – “Making English Learner Reclassification to Fluent English Proficient Attainable or Elusive: When Meeting Criteria Is and Is Not Enough” – got the attention of higher-ups and has now sparked a reexamination of districts’ policies. Relevance and actionability made the difference.

The William T. Grant Foundation has been flagging this problematic gap separating practitioners from researchers for several years. They don’t want to see time and money wasted on research that is impractical or irrelevant to practitioners. Their investment in research-practice partnerships looks promising. Let’s see if they can help bring to life the sort of practical, actionable research that pays off in the best possible form: good ideas that spread far and wide.