As education leaders declare their support for equal justice, and repeat their commitment to reduce the achievement gap, they are hard-pressed to answer the most direct questions about that gap in their own districts. “How big is the math achievement gap, based on students’ ethnicity?” “Does it grow larger or smaller as students move from elementary through middle school?” I imagine this must become an embarrassment.

As education leaders declare their support for equal justice, and repeat their commitment to reduce the achievement gap, they are hard-pressed to answer the most direct questions about that gap in their own districts. “How big is the math achievement gap, based on students’ ethnicity?” “Does it grow larger or smaller as students move from elementary through middle school?” I imagine this must become an embarrassment.

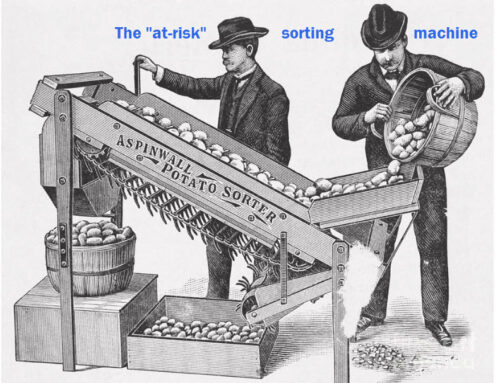

In California, the bad news is that inside the castle of K-12, we have a Dashboard that mismeasures gaps. It is often blind to big gaps, and overly attentive to small ones. It fails to flag gender gaps altogether. Its gap related blind spot is the result of two logic errors. (Those errors are compounded by disregard of the imprecision of test results, and more. But that’s another story.)

First, the Dashboard melds two things — the status or level of a measure, and its change from the prior year — into one. Taking two things that have no relation to each other, and blending them together, yields one meaningless result. The level and yearly change of grad rates, for instance, are independent of each other (aside from floor and ceiling effect). This is in contrast to a body-mass index which takes a person’s height and weight (which are related), and combines them into a single, useful measure for answering the question, “Am I the right weight for my height?” (You can read more about this logic error on a prior blog.)

Second, gaps are considered to warrant attention in district LCAPs when a subgroup of students’ results (grad rates or test scores, for instance) are two colors away from the “all students” color. Woah! How can you compare any group to the whole to which it belongs? If this were a question on the PSAT, I would guess that 95 out of 100 high school sophomores would recognize the fallacy. This fatal flaw is only made worse by the use of colors instead of numbers to size the gap. If the grad rate of “all students” is orange, you only have one color to go til you’re at the end of the CDE spectrum: red. (If you want to read a more thorough critique of this logic error, click here.)

So in California, education leaders, board members and citizens are unable to answer questions like these (although social scientists can):

- In which district is the math achievement gap in middle school grades smallest between Latino/Hispanic and white students?

- Which districts are seeing the smallest boy-girl gender gap in English language arts among high school juniors?

- Between 3rd grade and 8th grade, which districts are seeing their math achievement gaps diminish, and at what pace?

Due to the Dashboard’s flaws, education leaders’ gap knowledge is lower than it was 20 years ago. That’s because the Dashboard has handed leaders incorrect conclusions. And administrators who believe the Dashboard’s inferences are now more confident of its false conclusions because they came from a higher authority.

The good news is that in the world of social science, talented scholars are measuring variance wisely, and much better than they measured it 20 years ago. They understand the need to select the right method for measuring variance, and the right tools to measure it. They are able to judge the quality of the data they use to build evidence, and pay serious regard to its imprecision. They avoid introducing “noise” of distortions into the flow of signals from that evidence. They strive to exercise professional judgment when drawing inferences from that evidence.

Two bright lights in the social science world may convince you how far in the dark the castle of K-12 remains. David Figlio (Northwestern University) and his co-authors – J. Guryan, K. Karbownik, and J. Roth – published a startling discovery in 2014 about the relation of babies’ birthweights to their test scores when they grow up. They found the benefit of carrying babies to full-term was beneficial across all ethnicities and all household incomes. Measuring variances across subgroups was part of their findings made possible by the size of the evidence base — over 75 percent of Florida kids born between 1992 and 2002. The study led obstetricians to rethink the benefit and risk of early C-sections. (By the way, in examining your students’ test scores, did you ever consider that birthweight might explain some of the differences among students?) Click here to read an excellent New York Times article about this study.

Sean Reardon’s work at the Stanford’s Center for Education and Policy Analysis, and now at the Education Opportunity Project, has led to the creation of a research asset that many scholars have used to measure gaps. No surprise, Sean Reardon is a Professor of Poverty and Inequality at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education. His own research, often co-authored with Andrew Ho, is presented well in this New York Times article, “How Effective Is Your School District? A New Measure Shows Where Students Learn the Most.” It will give you a taste of the power of his methods and the clarity of his thinking. Even better, it provides you with an opportunity to see where your district stands. His opinion essay, “No Rich Child Left Behind,” will help you weigh the effect of gaps in household income in driving gaps in the pace of student learning.

With such brilliant work being done in the social sciences, why has California education policy failed to take advantage of it? Is the castle of K-12 surrounded by walls so high that social scientists can’t get in? Is the moat too wide? Are the inhabitants of the castle simply content to remain by themselves in the dark?