There’s a hypersensitivity in California school district offices to the use of student record level data. Internally, district leaders call it a litigation risk, deferring to the advice of their legal counsel. But externally, district leaders defend this in the name of protecting student privacy.

This rubs me the wrong way for two reasons. First, the internal motivation is the authentic reason. It is in the defense of the organization. This is not a noble cause, but it is a rational one. Why hide the self-interested rationale behind a screen of defending student privacy? Second, this purely defensive view should be weighed against the opportunity to play offense — to put student record level data to work to improve the quality of management decisions. It is this lack of regard for the opportunity that troubles me the most.

Nine Good Things That Could Result From Smart Use of Student Data

What benefits might a district enjoy if it put student record level data to work? Oh, let me count the ways …

- Improve the accuracy of identifying students who need reading help by combining assessments with teacher observations (and ending reliance on just one test).

- Reduce the waste of teacher and student time that results from failure to identify dyslexic students quickly. (See the CDE guidelines here.)

- Reduce your district’s error rate in overidentification of suspected English learners. (Whatever your prior error rate during the CELDT era, it is likely to erode further in this ELPAC era.)

- Improve your rate of reclassifying ELs as fully English proficient by combining several assessments and teacher observations, and comparing these to levels of English fluency attained by English-only students.

- Discover which middle and high school teachers are suspending students most frequently, and learn the degree to which their rates exceed the norms. (Perhaps reining in those teachers may do a lot to reduce your suspension rates.)

- Learn if students who attend school part of the day have common patterns that may explain their exit (e.g., same course, same teacher, same time of day).

- Audit teacher-assigned grades for evidence of bias, based on analysis of grading patterns over several years’ time.

- Learn the cost-per-class and cost-per-course to deliver instruction to your high school students, using actual teacher compensation and actual class size. This prepares you to meet criticism with evidence when you are challenged to show that you are actively offering equal opportunities to learn to all students.

- Discover the teacher and principal turnover rate over the last five years. If you see vastly different turnover rates across your schools, you could create compensation policies and labor contracts that enable you to move toward turnover rates that vary less across school sites.

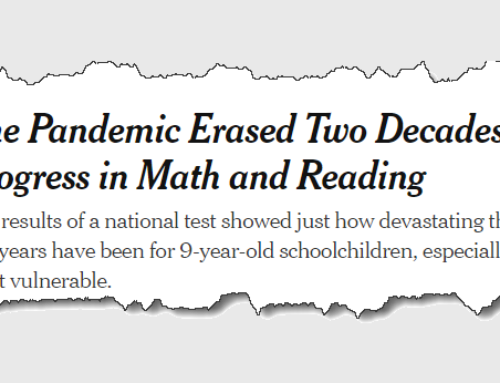

And that’s before I’ve had a second cup of coffee. If superintendents valued what they’d gain from intelligent and prudent internal analysis of student record-level data, they’d start using student record level data as other learning organizations do: to make smarter decisions.

Here’s the heart of it. Data has a cost. It consumes human time and district money. That data has zero value when you shovel it into your student info system, or convey it to CALPADS. It has value only when you build evidence from it, and use that evidence to gain a new perspective on what works, and what doesn’t. You’ve already spent real money to create student level data. Isn’t it time you invested a little more to build that data into evidence? What you’ll discover could save you money, keep you from doing harm, and enable you to remove barriers to learning.

Why District Leaders Tend To Be Overly Sensitive to Risk

In my opinion, two factors contribute to superintendents’ over-weighting the risk of being challenged for violating student privacy. First, they rely on lawyers to a fault. Lawyers should advise policy makers, not be given carte blanche to write policy. Some risks are worth taking. Some are not. If more superintendents just read the four-page policy paper written by the Data Quality Campaign, or the simple federal summary of the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act, they’d be better prepared to weigh their counsel’s advice and come to their own decision.

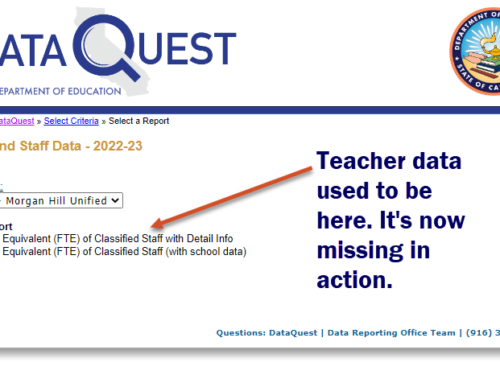

Second, the CDE itself has set an exceedingly strict policy that restricts researchers from most uses of student level CALPADS data. The CDE acts as if they are on a noble quest, protecting student privacy. In fact, they are acting as if they were kings of the castle of K12, treating student data as if they owned it. I’ve talked with two highly respected researchers whose requests were turned down on this basis (and I’ve been turned down, as well, for the same reason). This tone has colored the attitude of district leaders, who have defended their own restrictive policies by pointing to CDE higher-ups. In my view, this is a massive waste of a public asset. I say let’s put that asset to work serving the cause of smarter management of educational resources.