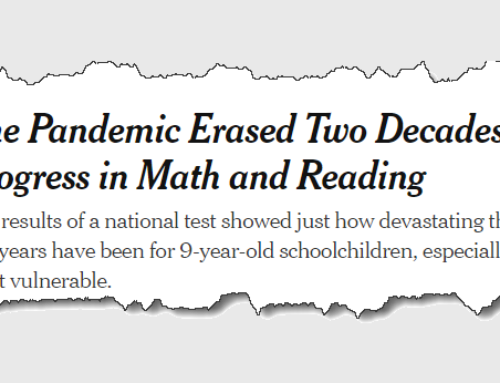

Educators almost everywhere rely on classifying and sorting their students. If a child is seven years old, she’s a second-grader. If a child’s parents earn less than 1.8 times the federal poverty standard, that student gets reduced price meals. If a student’s parents speak Spanish or Tagalog at home, and the student scores below a threshold score on the English language proficiency test, he is considered to be an “English learner.” This may be necessary, but is the sorting deforming our thinking?

I must ask this question. In the early elementary grade levels, who isn’t an English learner? What really distinguishes that young student dubbed an “English learner” is that she’s learning two languages at the same time.

California’s Terminology Problem

Note that in Texas, they no longer use the term “English learner.” Instead, they use the phrase “emerging bilingual student.” The U.S. Dept. of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition favors the term “multilingual learners.” This recap from SupportEd shows state by state, and for the provinces of Canada, how the terminology varies.

The SupportEd folks make a strong case for choosing terms with greater care: “When our terms for ML students don’t acknowledge differences in their language proficiency status, we lose the ability to measure students’ language and academic growth and achievement over time. Without these distinctions, we are unable to celebrate their success or adjust programs to better meet their needs.”

How true. When we forget that today’s emerging bilingual student is going to become tomorrow’s English-fluent student, we are likely to make two mistakes: (1) we’ll fail to see the mastery attained by reclassified fluent English proficient students who had been learning English years prior; and (2) we’ll overstate the deficits of students still considered to be emerging bilingual students. The designation “EL” is one that is intended to be impermanent. It should change. And it does for most kids.

The answer is simple. Use the “ever-EL” category in the denominator when calculating grad rates or test results.

California’s Classification Problem

The natural sciences consider the larvae, the caterpillar and the butterfly to be different stages of the same insect: Rhopalocera. They sit in the order named Lepidoptera. Consult this Wikipedia listing to see the details of the taxonomy of the butterfly. Why can’t we understand kindergarten-age multilingual learners to be the same species (ever-EL) as middle-school age “reclassified-fluent-English-proficient” (RFEP) creatures? They are simply different stages of the same human.

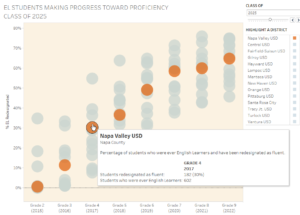

Portion of students who have ever been classified as emerging bilingual learners who have been reclassified as fluent-English-proficient. Results are for graduating class of 2025 in Napa Valley USD and 15 similar districts

When we revise our category assignment, we’ll see the success ever-ELs have attained. How about looking at reclassification rates by graduating class cohort? The visualization here [click here to see the live version] looks at Napa Valley USD and 15 other districts whose students are highly similar. What’s in the numerator? The number of kids in the grad class of 2025 who have been reclassified as fluent-English-proficient. In the denominator? The number of kids in that grad class who have ever been classified as EL. By end of grade nine, 431 students have been reclassified out of 665 “ever-ELs” in that cohort. The resulting view lets you look at the year-by-year portion of ever-EL students who have been reclassified. That tells you more than a simple 65 percent does. And you get to see it over eight years’ time for the same group of students. It is framed in the context of highly similar districts, so the hard work of these students can be seen compared to their “ever-EL” peers.

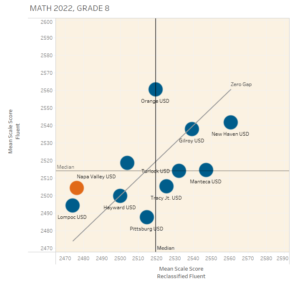

Results of RFEP and English-only 8th grade students on the 2022 CAASPP math test. Napa Valley USD is displayed in orange, and other districts displayed have highly similar students.

In many districts, RFEP’d students excelled, often exceeding the level of mastery of their English-only peers. Here’s one view [click here to see live version] of how that looks, comparing the math results of RFEP eighth-grade students in a handful of highly similar districts to their English-only fellow students. The diagonal line is the zero-gap line, where scale scores are identical. The vertical axis shows the English-only students scores in each district. The horizontal axis shows the scores of RFED’d students on the 2022 CAASPP math test. In the five districts to the right of the diagonal line, RFEP’d students average scale scores exceeded those of their English-only peers. For two districts, their scores were identical and sit right on that line. Isn’t it time we gave these students (and their teachers) the credit they deserve?

See these other blog posts for more comments on the trouble we create when we make logical and semantic errors when discussing emerging bilingual students.

Good news awaits if we stop measuring ELs and start measuring “Ever-ELs” (Oct 2018)

Two more Dashboard mismeasurements: English learners and grad rates (April 2019)

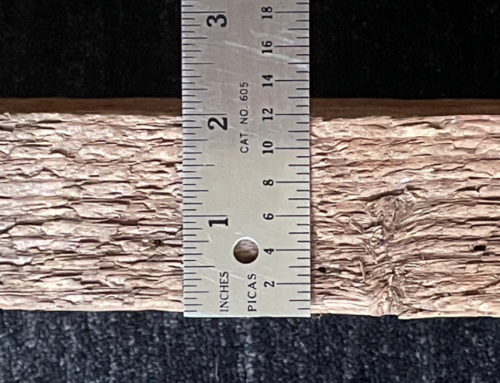

The hazards of labeling, or what the 2×4 can teach us about our words (Sept 2022)

This scholar knows how long-term English learners are created (May 2018)