Two more areas of mismeasurement are baked into California’s accountability policies, and are expressed in its Dashboard. One area is English learners. The other is graduation rates.

The transient category of “English learners”

I’d like to meet the policy people who believed it was legitimate, fair and meaningful to look at the year-to-year change in test results for students deemed to be English learners. This is a category designed to be a temporary one. It’s supposed to fit a student in one year, and not fit in a later year. So why compare EL students’ results in math in an elementary school (grades 3-5) in 2018 to EL students’ results in that school in 2017? When you combine the effect of natural mobility (fifth-graders in 2017 moved on, and third-graders in 2018 weren’t tested when they were second-graders) together with the effect of reclassification and mid-year transfers, you’re likely to be looking at two very different groups of kids in those two years. So, what exactly is the question that EL year-to-year comparison is intended to answer?

[To its credit, the CDE tried to switch to using the “Ever-EL” category. But they needed the approval of the U.S. Dept. of Education. On April 15, the federal higher-ups turned down the CDE’s request to group ELs and RFEPs together. If you want to read the feds’ turndown letter, you’ll find it in this State Board Information Memo that was posted April 19.]

For the same reason, the “free-and-reduced-price lunch” subgroup is also a temporary category. Students’ families’ incomes rise and fall above the line that is 1.85 times the federal poverty rate (about $46,400 a year for a family of four). The harsh economic downturn of 2008 and the recovery that followed, caused many families’ incomes to dip below that line, and then rise above it. If the students in the subgroup change year-to-year, why compare their results?

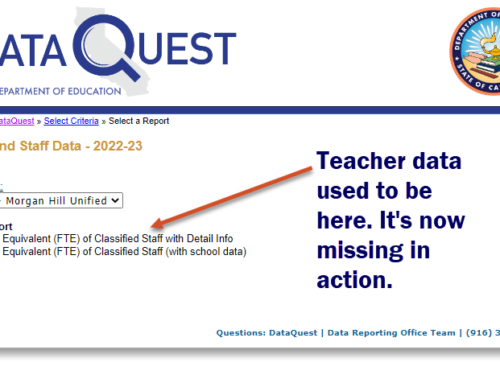

Paul Warren, in his June 2018 report published by the Public Policy Institute of California, asks the CDE a smart question. Since the CDE is in possession of every student record in CALPADS, and every student’s test record, why don’t they report truly stable student graduating class cohorts when describing year-to-year change? Other states do just that. Why not California?

Reporting graduation rates while ignoring differences in district’s graduation requirements

Oh, boy. This is a problem of measuring the quantity of grads, without regard for the quality of their courses of study. Other states have tiered diplomas, defined uniformly statewide. This makes meaningful comparisons possible. But in California where districts do their own thing, comparing grad rates is a very messy matter.

Those of you inside the front office and who lead high schools know what a difference your grad rate can make to your schools’ reputations. Some districts require just 210 units. Others require 240. (By the way, California’s Ed Code requires just 130 units.) Some districts require A-to-G course requirements be met for graduation. Others do not. Some districts offer credit recovery cautiously and conservatively. Others game the system, telling lagging students that they can complete an 18-week course in 18 hours.

With “graduation” meaning such different things in different districts, what are you learning when you compare grad rates? Until the SBE and CDE define the rigor of courses, the passing grades, and the number of real units required for graduation (not 130), the Dashboard will continue, at best, to mismeasure (inaccurately compare) districts’ and schools’ graduation rates, and at worst, incentivize them to game the system. Quality and quantity need to be connected.

Historical footnote … When California had a high school exit exam, there was a state level standard that defined the level of mastery students had to show in order to earn a diploma. Unfortunately, that standard was pegged to 8th grade algebra and 9th grade level English/language arts. But it was a common standard. If students couldn’t meet it, they couldn’t get a diploma. So there was a common element that all districts shared when deciding who could graduate. While this didn’t make for a uniform meaning to all districts’ grad rates, it imposed at least a minimum standard that all seniors had to satisfy in order to get their diplomas.

A Hopeful Forecast

The policy higher-ups can do better. Researchers and scholars have been feeding good ideas to the policy folks for years. The idea of retiring ELs as a category and replacing it with a category of “Ever ELs” has been in discussion for at least two years. Why not add a California “Ever EL” category, while keeping the federal folks happy with their peculiar embrace of the old EL category?

In the meantime, districts and county office people can take seriously the notion of local control, and begin to create their own local measures that correct for the mismeasures that are baked into the Dashboard. Get going, get local, and measure smarter.

Paul Warren’s suggestion that the CDE make use of the longitudinal power of CALPADS, and infer progress by measuring the same kids in the same school and district over time makes the most sense of all. With a new governor who believes, we hope, in measuring the right things the right way, and some new State Board members whose thinking may be less encumbered, perhaps a turn in this direction is at last within reach.

To read other blog posts on the errors and illogic of the California Dashboard, click here.