The New York Times assigned reporter Sarah Mervosh to make sense of the 2022 results of the Nation’s Report Card, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Her headline (which may have been written by the copy desk) twisted results into a New York sized pretzel: “The Pandemic Erased Two Decades of Progress in Reading and Math.”

What the pandemic erased were lives. It did not have the power to erase knowledge from kids’ brains.

To be fair, the NYT wasn’t the only paper to headline the story this way. The74’s story, written by Kevin Mahnken, offered a similar headline: “Nation’s Report Card: Two Decades of Growth Wiped Out by Two Years of Pandemic.” Really? “Wiped out?” This is the language of war reporting.

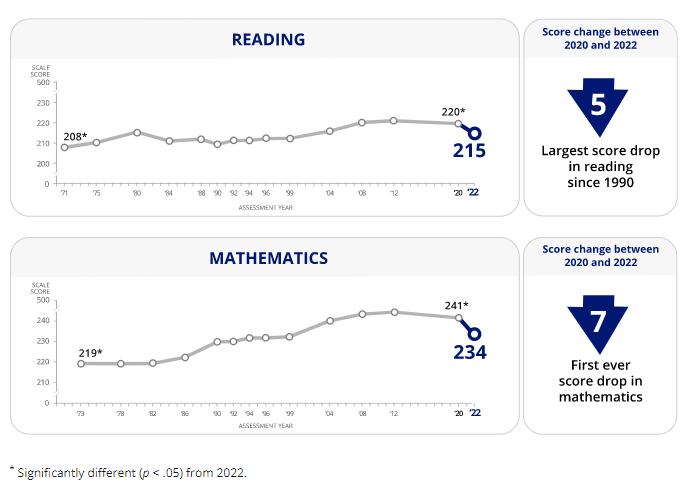

Credit: National Assessment of Educational Progress

The first two paragraphs of the NYT story added even more drama to the story:

“National test results released on Thursday showed in stark terms the pandemic’s devastating effects on American schoolchildren, with the performance of 9-year-olds in math and reading dropping to the levels from two decades ago.

This year, for the first time since the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests began tracking student achievement in the 1970s, 9-year-olds lost ground in math, and scores in reading fell by the largest margin in more than 30 years.” [italics are my own]

Whatever math knowledge and reading skills were already in the heads of kids who in 2019 were three years younger remained there in 2022. The kids who took the NAEP in 2022 did not really lose “ground in math” and reading. They simply scored much lower than 9-year-olds scored in 2020, and other 9-year-olds before them.

What are the right words to describe the pandemic’s impact?

What the NAEP results showed us was the lack of growth of students who were not in school for a year or two. This absence of growth is not the same as the loss of knowledge. The bad news: these kids who are now ten years old will be tackling subject matter in grade five that is likely to be over their heads. They missed a year or two of schooling while the world stopped, human contact outside their families was minimized, some people got very sick, and others died. The good news (if their districts adjust their curricula): many will tackle the subject matter they missed with more developed brains and will be likely to master the material they missed at a faster clip than they would have otherwise. Expect a faster learning rate for many. But expect a slower learning rate for others.

What the NYT headline got wrong is that it compared the 9-year-olds of 2022 with the 9-year-olds of 2002. Why do that if their school experiences are entirely different? It leads us to think these two cohorts of students (one group 9-years-old and another group now 29-years-old) are in some kind of race. Nor is the math knowledge of nine-year-olds like a granary vault. It hasn’t been eaten by mice.

The more meaningful comparison would have been to ask how the state of reading skill and math knowledge of 9-year-olds in 2022 compared with their own mastery of those subjects prior to the pandemic, when they were 7-years-old.

Wait. There’s more good news in the NAEP results. They show us what being in school does to the math and reading skills of 9-year-olds. If they’re in school for five years (K-4), they score much higher on NAEP than if they’re in school for only three or four years.

What should be measured is district effectiveness in adapting to students’ readiness to learn

I get hopped up about misstatements like this because the sloppy use of words by newspapers and other media organizations is contagious. It leads others to commit the same mistakes. And sloppy words belies sloppy thinking. Yes, of course, the pandemic delayed learning of many kinds. But delays are not the same as losses.

Many kids learned other things during the months they weren’t in school. Is anyone taking stock of those gains?

Measurement attention should be going to school districts’ responses to the interruption of schooling. Smart responses will account for the absence of instruction for most kids for a year or two. Shifting what’s taught to kids at each grade level would be the response of a district that’s adaptive, flexible, and kid-centered. Not shifting, and requiring teachers to deliver the same lessons they delivered to kids of the same age and grade level prior to the pandemic, would be an example of not adapting, not being flexible, and being a teacher-centered system.

New times call for new metrics. Let’s get started.

====================================

Look for the book I wrote with Jill Wynns, Mismeasuring Schools’ Vital Signs. Routledge is our publisher, and they are putting the book on-sale September 29.