Wendy Lopez and Kateryn Ochoa, have a problem with their district, West Contra Costa USD (WCCUSD). But it’s not the usual sort. These two, one a parent and the other a student, want current data in their district’s LCAP. They are not taking the district’s excuses as a suitable answer.

When they asked politely for this data, their LCAP parent and student committee didn’t get it. So they turned to Public Advocates, the public interest law firm that helped win the Williams lawsuit in 2004 together with the ACLU of Southern California. For good measure, a private law firm, Mayer Brown, LLP, also stepped in on behalf of the plaintiffs, free-of-charge. Apparently, access to accurate, current data is of high interest to many.

With many districts now seeking “stakeholder engagement” with new enthusiasm, district leaders should heed the words of student Kateryn Ochoa: “How can we participate in local decision-making if we don’t have data about how students are doing and feeling?”

The particulars of this challenge are well explained in this news article by reporter Theresa Harrington on the EdSource website, published April 23, 2018. The details are worth reading. This leaves me free to offer a different perspective on the value of information.

Wendy Lopez and Kateryn Ochoa and their fellow members of the district LCAP parent-student team are part of a long line of citizens who take their district’s promises and the laws that surround them seriously. One of the types of promises that districts make is to tell the truth with numbers. County offices of education make a similar promise, also enforceable by law, to compel districts to do just that. This is why the lawyers representing Ochoa and Lopez also filed a Uniform Complaint against the Contra Costa CoE for failing to compel WCCUSD to publish updated data in their LCAP.

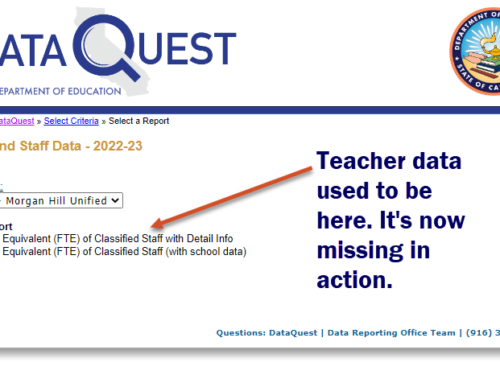

Access to information, in fact, was part of the Williams litigation, which called for county offices to monitor SARCs both for timeliness and accuracy. In fact, all three of the Williams’ areas — the condition of buildings, textbooks and teachers — created information. Access to information was part of Prop. 98, passed in 1988, which assured districts and community colleges to no less than 40 percent of the state budget. In return, districts were obligated to publish school accountability report cards.

Districts that hope to earn an “A” for effort in meeting their data disclosure requirements under law should not be surprised when they discover that citizens have handed them a “U” for Uniform Complaint Procedure. Data is the raw stuff from which information is built. That information becomes a way in which citizens determine if their districts are doing the right thing. Citizens have a right to that data, and it has to be correct, delivered by dates set by law or policy, and be published in a form that’s accessible and understandable. (There is federal law and policy on these two standards.)

This won’t be the last chapter in the Lopez-Ochoa challenge. I predict that other LCAP parent-student teams will be stepping forward in the months ahead to file similar complaints.

My advice to district leadership and governance teams is simple. Take data seriously. This means budgeting for it, and more. Gather it with care. Key it correctly to your student information systems. Transmit it accurately to CALPADS. Generate output that you proof-read before publication. Publish it prior to deadlines. Let your staff, students, parents and community know when you’ve met these commitments.