I just returned from the annual conference of the California Education Research Association, feeling both pleased and disturbed. What pleased me was the conference theme itself: the power of visualizing data. That’s an entirely suitable topic for the members of an organization in charge of communicating the meaning of quantitative measures.

What disturbed me was that the presenters I heard (with the exception of Jenny Rankin, the first day’s keynote speaker … and in the interest of full disclosure, a member of our consulting team) reduced data visualization to a design solution of a communication challenge. Their arguments go something like this.

- Tables of numbers don’t reveal their meaning to anyone but math geeks;

- To reach everyone else, visualize the data;

- Avoid chart junk and follow good design principles;

- Then use your visualizations to tell a story that grabs people emotionally.

Discovering the real story the data holds requires thinking

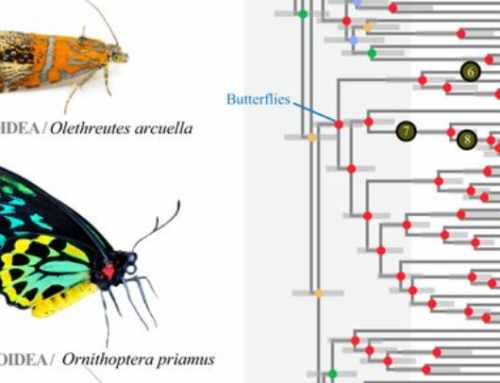

I believe this simplistic argument misses the hard part. How do you know what the story is? The numbers don’t speak for themselves. You have to interpret them. After all, data visualization was a method created by analysts and economists to tell a story. John Tukey, in his 1977 book “Exploratory Data Analysis” emphasized the use of data visualizations to explore patterns, often of two or three factors in relation to each other. It requires reasoning, logic, creativity and more.

Any education analyst who hopes to tease out a reasonable story from the evidence requires four other elements to tell a data story effectively.

- An active curiosity that isn’t easily satisfied;

- A good b.s. detector for weak logic and poor quality data;

- A detective-like skepticism of the easy interpretation;

- A tolerance for ambiguous evidence.

An example may serve to show why these human qualities are needed to explore evidence in order to build a reasonable story.

Example: Grad rate problems land your district’s comprehensive high school in CSI

Example: Grad rate problems land your district’s comprehensive high school in CSI

Your Central Valley high school’s grad rate in 2019 was 65 percent last year. Obviously, your board isn’t happy with this news. But it’s not so different from the 69 percent grad rate of the prior year. But last December, the CDE’s Dashboard has flagged your school as “red” for both grad rate and chronic attendance. Now your high school is also in CSI. So now your staff’s demoralized and your town’s leaders are troubled. What’s the story? People want to know.

Your grad rate reflects a lot of human events. You need to make them clear.

Mobility. You know that your high school students in prior years have been graduating at rates between 75 and 85 percent for years. For a Central Valley community, where families move more frequently, chasing agricultural and service jobs that aren’t steady employment, you know that students who transfer into your high school in their junior or senior year are more likely to not graduate in four years.

No summer credit recovery. Your board passed a policy to discontinue credit recovery five years ago, when they discovered that it was being used in all the wrong ways. Students were being told they could cram a week of learning into two hours of work in the library. Books and teacher’s aides, baby-sitting students in a “self-guided” learning program, had become the way that lagging students were treated to a summertime “fast path” to a diploma.

No use of the 130-unit rule. Education law allows for students to receive a diploma after completing just 130 units. Some districts allow their lagging students to graduate if they’ve completed those units successfully. Not yours. Your board ruled out that “low road” option years ago when they discovered that a prior superintendent was more eager to hand students a diploma than deliver a real education.

No push-outs of marginal students. Your district has not been quick to transfer marginal students out of your comprehensive high school over to your continuation high. Your policy has been to keep them enrolled, and your people have worked hard to help them succeed. So where other high schools “push out” the students least likely to graduate, your high school has done the opposite: kept those kids enrolled, and invested in their academic success.

Your five-year graduation rate is healthy. Your people and your district’s policies to help struggling students led you to allow them an extra year to graduate. So your high school’s five-year grad rate is 83 percent, an entirely respectable number in the Central Valley. But the CDE Dashboard hasn’t given credit for this, despite ESSA’s requirement that they do so. And the hard line to determine a CSI high school is 67 percent grad rate. So that leaves your high school and your district looking bad.

A large group of immigrant families moved to your town in 2013. The arrival of several dozen families from Chiapas, Mexico, brought a lot of students into your district who had been under-educated. Some were not able to read and write Spanish fluently. No surprise, half of the fifth-grade students in Mexico’s elementary schools are unable to read a chapter book. In addition, some of the families were indigenous Mixtec speakers. When their children arrived, many were adolescents, who soon ended up in your high school. Their path to graduation was clearly going to be a longer one. And there were enough of them that they pulled down your grad rate.

So how would you “visualize” this data story? Whatever your approach, you’d make clear that students are not widgets – identical two-legged life-forms. They are humans, and their differences make your graduating class cohorts different, sometimes to a large degree. So your data story would need to account for all these factors, with each cluster of students who comprise your cohorts having a story of their own.

What attributes do analysts need in order to build a real-world story from evidence?

Here’s how the four qualities of analysts would help you build a story.

A passion for a good riddle, and an active curiosity that isn’t easily satisfied … the riddle is how to counter the verdict of officialdom. Your curiosity is the fuel that drives you into the messy, human factors that make your counter-arguments meaningful.

A good b.s. detector for weak logic and poor quality data … the weak link in the logic chain is that a grad rate is a universal measure, one that enables an outside authority to draw a magic line at 67 percent and then assert that any high school with grad rates below that line deserves to be in the dog house.

A detective’s skepticism of the easy interpretation … this keeps you from being intellectually lazy, and accepting the Dashboard’s convenient conclusions and the U.S. Dept. of Education’s line in the sand at 67 percent grad rate.

A tolerance for ambiguous evidence … a data point may look clean, crisp, certain. But it may hide fuzzy qualities: uncertainty, imprecision, estimation. You need to be ready to grasp fuzzy data with gentle hands. Matching the firmness of your grasp to the fuzziness of your data is the way to make reasonable sense of what you’re holding.