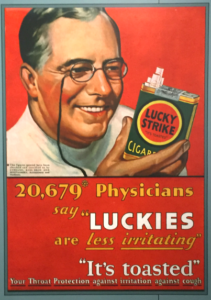

The errors of the medical profession became visible only when evidence of harm from cigarettes was accepted and interpreted correctly.

In John Hattie’s book, Visible Learning, he asks whether teaching “… can shift from an immature to a mature profession …” He comes to this stunning question after looking at the practice of medicine in the 1890s, and he begins by quoting Lewis Thomas, author of Lives of a Cell. “It is hard to conceive of a less scientific enterprise among human endeavors. Virtually anything that could be thought up [by doctors] for treatment was tried out at one time or another, and once tried, lasted decades or even centuries before being given up.” (Lewis Thomas, Lives of a Cell, 1979, page 159).

Hattie then turns to the profession of education.

“Thomas was referring to the study of medicine and noted how evidence-based medicine was the mechanism for driving out dogma, as dogma does not destroy itself. The evidence-based revolution came through repugnance and pressure from groups that were adversely affected by the poor quality of service in the medical profession. Maybe legal cases about equity in outcomes across various ethnic groups, poor service by teachers, clinical trials of new educational treatments, and a set of international standards and expectations for outcomes from schooling may be the catalyst for change and improvement in education. More of the same is certainly not the answer. The key question is whether teaching can shift from an immature to a mature profession, from opinions to evidence, from subjective judgments and personal contact to critique of judgments.” (John Hattie, Visible Learning, 2009, pages 258-59).

Hattie’s challenge led me to wonder if today’s debate about how to teach reading might be the moment when education makes a quantum leap in maturity. Like medicine, which became a modern science when it shifted to evidence as a basis for knowledge, education could now make the leap. Today’s reading debates, a clash between advocates of balanced literacy and structured literacy and between advocates and opponents of the science of reading, was one I recall from the 1980s. At that time, we called it the whole-language-versus-phonics wars. My own children were in school then. California’s state school chief, Bill Honig, was a vocal advocate of whole language, and was opposed by phonics advocates like Marion Joseph. After Honig left public office in 1993, he switched teams, declared his errors, and started the Consortium on Reading Excellence (CORE) to teach teachers how to teach reading based on a firm foundation of phonics and phonemic awareness.

The debate over how to teach reading is long-lived

I later learned that when I was a child in school in the 1950s, a similar debate raged. If you don’t believe me, pick up the book written by Rudolf Flesch in 1955, Why Johnny Can’t Read. You won’t have trouble finding it. It is still in print, as is the 1983 sequel, Why Johnny Still Can’t Read.

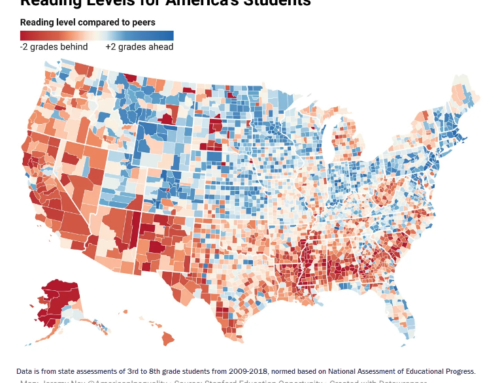

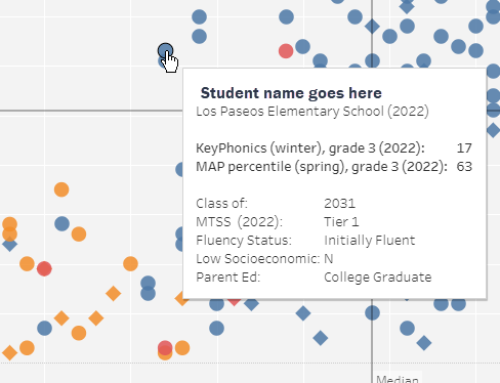

Now, 68 years after publication of Why Johnny Can’t Read, the same arguments are still raging. Little has changed except the people who champion both causes. Yet the fact base has changed enormously. Neuroscience has enabled us to see how the brain works when people speak, read, write and learn. Education measurement’s advances enable us to see which skills struggling readers have not yet mastered. The National Adult Literacy Study has enabled us to see the county-by-county view of adults who are unable to read a “help wanted” ad or apply for a driver’s license.

It took 100 years for statistics to move past “statistical significance”

Will this enable those who manage teaching and learning for a living to make a quantum leap, and elevate their profession? I am hopeful this may occur because I have seen it happen in the field of mathematics. A decades long debate about the concept of “statistical significance” was declared resolved by the editors of the professional journal of the American Statistical Association. In their March 2019 issue, they published 43 essays, each making a different case for retiring p-values (shorthand for “statistical significance”). In a lead editorial, the editors drew a line in the sand. They called on members to stop using the term “statistical significance” altogether, warning members that if they submitted articles for publication using p-values, editors would reject the articles.

Considerable courage was required to end what they called “the statistics wars.” Professional statisticians had to admit that a core principle of their field was used incorrectly so frequently that its use should be ended. They had to admit that its misuse caused great amounts of human harm. Among the most articulate and vocal of the critics of “statistical significance” were two scholars, Deirdre N. McCloskey and Stephen T. Ziliak, who documented harm caused by its misuse in the fields of economics, health care, pharmaceuticals (remember Vioxx), psychology and educational testing. The title of their 2008 book is worth citing in full: The Cult of Statistical Significance: How the Standard Error Costs Us Jobs, Justice and Lives. (For a 15-page summary of the core ideas of their book, I recommend this essay.)

Self-critical reflections of many reading educators may enable education to grow up

How similar is the challenge facing education leaders, superintendents, curriculum and instruction directors, and teachers of reading today. Thanks to Emily Hanford’s terrific reporting, I have heard interviews with teachers filled with regret at causing harm misteaching reading — teaching kids to read by guessing the word rather than sounding it out. Their pain at having caused harm, and the pain of those who taught them in teachers’ colleges and schools of education, is not unlike the pain felt by those economists and scientists who caused human suffering by misusing principles of statistical significance. (Click here to find her podcasts.) Emily Hanford has interviewed educators who have admitted the errors of their ways. Can they create the critical mass required to tip their profession into the moment of self-reflection and self-correction that statisticians and doctors have braved?

Education management has a moment now to answer John Hattie’s challenge. It can become a more mature profession by seeing the error of its ways, make public apologies, and stop misteaching reading. Bill Honig did it. Can today’s leaders do the same?

To learn more about the education profession’s resistance to evidence, and the harm it causes, see the book I wrote with Jill Wynns, Mismeasuring Schools’ Vital Signs.