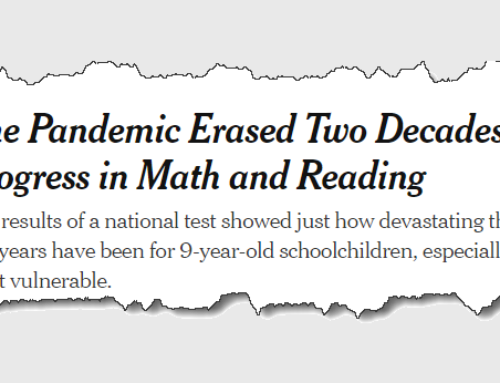

The appearance of the COVID-19 virus has led to the sudden disappearance of the CAASPP/SBAC tests here in California. Other states have also lost their spring standardized tests. Is this a moment to dread the loss of one estimate of students’ academic progress? Or is this a moment to welcome the use of other measures to estimate students’ level of mastery?

Consider the possibility that this is a moment to embrace. You are free of the CAASPP/SBAC. (Little secret: it was never designed to help teachers guide their instruction student by student.) What else might you use to estimate the pace of your students’ progress? Even better, what other evidence of student learning would you like to have in hand?

Stretch your mind for a moment, and imagine you were a captain of a ship at sea in the 1600s. Imagine you lost your compass. Navigating requires a map, a compass and a sextant. No compass would mean you’d no longer be able measure the direction your ship is headed. But would you have alternatives? Of course. The sun’s movement across the sky, and the position of the stars, are constants. Knowing your last position on the map, and knowing your ship’s position in relation to the sun and stars, would give you an approximation of the direction you’re sailing.

Stretch your mind for a moment, and imagine you were a captain of a ship at sea in the 1600s. Imagine you lost your compass. Navigating requires a map, a compass and a sextant. No compass would mean you’d no longer be able measure the direction your ship is headed. But would you have alternatives? Of course. The sun’s movement across the sky, and the position of the stars, are constants. Knowing your last position on the map, and knowing your ship’s position in relation to the sun and stars, would give you an approximation of the direction you’re sailing.

What other measures of student learning are in your hands?

Ask yourself what alternative measures of student learning are available to you now. If your district, like most, includes elementary schools, you are teaching students how to read. No doubt, you are measuring their progress. Your assessments may include Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS), Fountas and Pinella (F&P), AIMSWeb, or the NWEA MAP Lexile subtest of their ELA assessment. Together with whatever dyslexia universal screening you’re doing, combined with teacher-assigned grades, you have a lot of evidence in your hands. Time to get your cabinet to the table, clarify the questions you want to answer, summon your assessment director, and start using the evidence in hand fully.

Note well that I’m suggesting you pause before you start mining the evidence. Pausing to clarify the questions you want to answer is the necessary precondition to making intelligent use of the measurements you have in hand. The two steps at the heart of intelligent analysis are (1) starting with the right questions, and (2) building the evidence that is best suited to answering those questions. This is not about data or statistical transformations of that data. It’s about thinking clearly.

What else about student learning might you want to learn?

James Popham, in his terrific book, Unlearned Lessons (Harvard Education Press, 2009), asked why educators fail to measure students’ attitudes about learning. In fact, he dedicates an entire chapter to exploring this question. In chapter four he poses this question:

“If a child masters mathematics cognitively, but learns to detest mathematics in the process, is the child well served educationally? If kids learn to become genuinely skilled readers, but end up regarding reading as a wretched and repugnant activity, should educators really be elated with this result?”

With all the attention now given to social-emotional learning, you’d expect that assessing students’ attitudes toward learning itself might become popular at last. But instead of seeing questionnaires that provide insight into students’ curiosity, or their opinion of their teachers’ efficacy, I see questionnaires about students’ opinions of their own abilities to learn. Internal psychology of the student is probed. Why not measure students’ curiosity, and gather evidence of voluntary learning activities — the kind kids do on their own?

Popham goes on to explain practical ways to measure these things. He asks, why not ask students when they return in the Fall what they read over the summer: books or magazines or comic books. And then ask them how much they read. And when they read. And to what degree they liked it. And what they liked best. And whether they recommended any of their readings to friends.

On page 85, Popham also offers a clever questionnaire, titled “My View of School: An Illustrative Affective Self-Report Inventory.” Students are asked to be truthful, and told to not put their names on the questionnaire. It is anonymous because responses become meaningful in the aggregate. It is practical: he notes the cost is low and the value of the insights are high. And it is actionable: students’ answers can lead to teachers changing how they teach. Again, from Popham:

“It is possible for teachers to snare meaningful insights about their students by reaching inferences based on the entire groups’ responses to anonymous self-reported affective inventories.”

What a perfect moment to select a few new local priorities, and create smart measures that will help you see how you’re doing at meeting your goals. Popham has shown the way. You can be fast and frugal in this and gain a whole new view of the effect of schooling on your students.

Use your freedom to exercise local control

For more than five years, California education leaders have heard the phrase “local control” from policy chiefs and government big wigs. Isn’t this the moment to take their words seriously? At the moment you’re unable to use the state’s assessment instrument (the CAASPP/SBAC), you either choose to build other evidence, or surrender to the absence of ready-made results. I urge you not to surrender. Rather, think like a captain of a ship at sea whose compass just got washed overboard. Take stock of what estimates you now have, gather whatever new estimates you consider helpful, and return to the job of steering your ship safely into port.