As you are putting finishing touches on your district’s LCAP or your site’s SPSA, I hope you’re valuing your interim assessments more highly. With this April’s CAASPP/SBAC testing cycle scrubbed, that’s all you’ll have to work with next year when drawing conclusions about student learning. Making sense of those results at the school or district level requires the same knowledge you need to make sense of the CAASPP/SBAC: the imprecision of the results, the meaning of the metric you’re using, and the benchmark you’re using to measure these results against. Chances are, that benchmark is a norm.

But what are norms, really? Where did they come from? To make proper sense of your students’ scores, you need to know who established those norms, how and when they did it, and for what purpose.

A BRIEF HISTORY LESSON OF NORMS RUN AMOK

In the days before the California Standards Tests (CST) and CAASPP/SBAC, California students took tests that were norm referenced (the CLASS, the SAT-9 and the CTBS). That means that students’ scores were compared against the results of a panel of thousands of students, who took that test before. Students’ results were expressed in any one of several forms, but it always included a national percentile rank. That number let you know that your students scored above some percent of other kids in that national norm group.

This NY Times article repeated the allegation by Dr. Cannell that test results were “voodoo statistics.” (February 17, 1988)

Each state made its own choice of test instruments. But all the companies which built those assessments invested in big panels of students whose scores served as norm groups. Those norm groups were costly, so testing companies invested in renorming as little as possible.

As students and teachers became more familiar with these tests, students’ scores climbed. “Score creep” entered our vocabulary. Eventually, so many states’ education chiefs were boasting that their kids had scored above average (meaning above the average scale score of the norm group), that the claims started looking implausible. Indeed, some were. In 1988, a West Virginia doctor, J.J. Cannell, got hopped up and wrote a book: How Public Educators Cheat on Standardized Achievement Tests: The “Lake Wobegon” Report. His book caught the attention of reporters, and after one of them ran a story on the Associated Press wire, Dr. Cannell went on the talk-show circuit. One result was a loss of credibility of education leaders and the tests they relied upon. Another result was that a lot of superintendents started paying more attention to the norms used by the testing companies they’d hired. (For more background on the Lake Wobegon report, I recommend this Education Week article.)

INTERPRETING TEST RESULTS REQUIRES CONTEXT

When the CST was introduced in the late 1990s, students’ scale scores were interpreted against a set of criteria that a panel of experts believed to be equivalent to five levels of mastery of the state’s new standards. “Proficiency” became the term of choice. While no impaneled norm group was used to measure students against, a group of students who took field tests established the basis for experts drawing lines, called cut-scores, that separated those five levels of proficiency from each other.

Where did the norms go? They were still there, but much harder to see, especially because education leaders kept asserting that the CST was criterion-referenced, not norm-referenced. But the norms, in effect, were drawn by the experts who decided what constituted the magic lines separating one category of “proficiency” from another. My point is not that it was done in secret. My points are: (1) these lines were the result of human judgment (and fallible); and (2) the field test they used was their norm group. That field test and their judgment constituted the equivalent of a norm against which students were scored.

By the way, the fallibility of their judgment resulted in visible errors in third grade English/language arts. The experts set the mark of proficiency too high, which resulted in a lower percentage of third-graders meeting that mark than in grade two or grade four. Norm group errors were also visible in the SAT-9 that preceded the CST. In that case it was a ninth-grade norming error.

WHAT NORMS DID THE CDE BUILD INTO CALIFORNIA’S DASHBOARD?

Today, the CDE and the Smarter Balanced consortium groups students’ CAASPP/SBAC scale scores into four categories. The term they use today is not “proficient” but “meeting standard.” The Dashboad’s subsequent spreading of results across five levels of colors is similar to what psychometricians did in the CST era when they spread students’ results across “proficiency bands.” Human judgment was the basis for deciding what portion of schools and districts would be in the bottom two color categories. And at the end of the day, there’s only a certain proportion of schools and districts that can be flagged for “assistance” and only so much money to be spread around.

The magic lines drawn by human experts inside the CDE that determine the trouble zone for academic achievement, chronic absences, graduation rates and more, are revealed in the Technical Guide to the 2019 California School Dashboard. Somewhere within those 274 pages you’ll find the range-and-frequency values for every measurement that appears in the Dashboard. In December 2019, the CDE higher-ups applied those Dashboard’s interpretations, putting 333 districts in the unhappy zone of “needing assistance.”

If your district is one of them, you’d do well to understand the arithmetic that resulted in your “Differentiated Assistance” status.

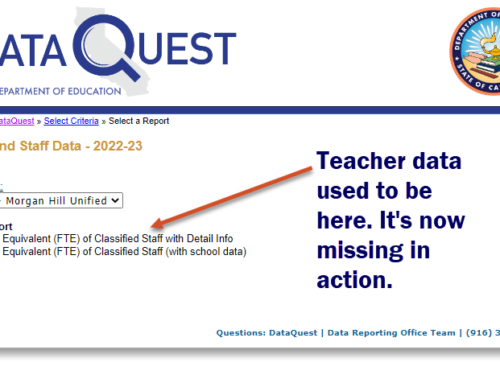

WHAT NORMS ARE YOU RELYING UPON IN YOUR DISTRICT-WIDE ASSESSMENTS?

I’ve seen many LCAPs and SPSAs in the last ten years that relied all too quickly on norms to determine where their students’ results were soaring and sagging. Norms this important should be explicit in your plans. With NWEA recently releasing their new norm tables for 2020, perhaps it’s time to take a look at this critical yardstick that your students’ scores are being measured against. (I’ll use NWEA as an example, but all test firms have norms of their own.)

NWEA selected a sample of its 12 million student records to construct a norm group. And they selected those samples to match the demographic profile of the students in the U.S. So if your district or school resembles the profile of the U.S. students in grades K-12, you’re in luck. But if not, then your students’ results are being compared to the results of students who are to some degree not like your own. Is this the way you want to measure growth?

If that’s not your preference, NWEA gives you an alternative: conditional growth. This takes into account the starting scores of your students, and of course their grade level and subject. This allows for different students to attain different levels of expected growth. When you roll that up for a school or district over time, you have a norm that’s intended to be tightly matched to your students.

Choosing which norm suits your purposes is not a small matter. It’s one of those big choices that you should set by policy. Get everyone interpreting test results the way you think is best, against the most appropriate norm group, and you’ll have harmony where it counts.

Moral of this story: pick your norms with care, or prepare to get lashed with a rubber ruler in the village square.