What do the CDE and CDC have in common? They share a problem counting people correctly.

What do the CDE and CDC have in common? They share a problem counting people correctly.

The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC’s) counting problem was that they were pressed by the White House to boost their testing numbers. So a deferential functionary in the Centers for Disease Control had the not-so-bright idea of merging two utterly different tests: the swab test and its equivalents that look for the presence of an active COVID-19 infection, and the blood-based test that look for the presence of antigens that indicate that a person got over an infection. The swab test identifies someone who has an infection now. The blood-based antigen test identifies someone who had the infection before. By counting both tests, the CDC officials gave the White House a higher number of “coronavirus tests given.” That led to a slew of misunderstandings. Thankfully, after a lot of critical attention, CDC officials reversed course on May 14, and corrected their error.

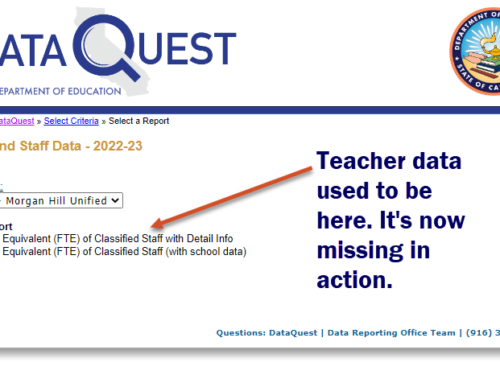

The California Department of Education’s (CDE’s) counting problem still persists. Sometimes the problem is apparent in small things, like how to count five-year graduation rates. But at other times, the problem is apparent in big things, like determining achievement gaps. The consequences are also big. These counting problems mean that all too often the wrong districts are being flagged for Differentiated Assistance and the wrong schools being sent into Comprehensive School Improvement. This means that all too often, money and time are being spent in the wrong places for the wrong reasons.

But the motivation of the two agencies are entirely different. The CDC is politically motivated to please its boss. The CDE’s motivation is not political. But I am unable to guess what its motivation might be. This leaves me with a hunch that the CDE’s counting errors are just the result of flawed human judgment. Somehow, I don’t find this to be reassuring.

I’ve written before about this noise that the CDE introduces into the Dashboard’s signal. You can find a half dozen blog posts about the Dashboard’s flaws from this link. At the end of January 2020, I delivered a presentation at the ACSA Superintendents Symposium. I’m not the only person to call attention to these errors. Paul Warren, who recently retired from the Public Policy Institute of California, did so in a June 2018 report. Morgan Polikoff of USC’s Rossier School has also raised objections. And the CORE Data Collaborative’s 125 districts have quietly walked away from the Dashboard and invested in better measures of their schools’ vital signs.

The irony is striking. The CDE and State Board created a new accountability system to go with the new Local Control ethos. Yet they centralized control of interpreting schools’ vital signs more strongly than they did during the API era. Their leaders, especially prior SBE head Mike Kirst, defended the new system as superior to the API-centered prior system. The CDE and State Board aimed to replace the API, a single number, with many measures of many dimensions of the vital signs of schools and districts. Is the end result better? I think not. In the end, the Dashboard, with its use of colors instead of numbers, its melding of status and change, and its illogical way of identifying gaps, has resulted in a less accurate, less valid, less understandable set of signals about the condition of schools and districts than we had before.

The defenders of the Dashboard have often called it a “work in progress.” Can an accountability system that can’t count be considered progress? At best, the architects of this Dashboard aimed at something more ambitious. But their plans were flawed, and their execution sloppy. The end result is lower credibility of the CDE itself, increased skepticism among the public in the judgment of district leaders, and damage to reputations of schools and districts that have been flagged as laggards in error. Other damage must include the false negative results, failing to identify schools and districts with big problems that get a pass because they are misdiagnosed by the Dashboard.

The good news is that districts and county offices can fix this by demoting the place of the Dashboard in their plans, and building their own bases of evidence to take stock of how they’re doing. Want some guidance on how to do that? I’m ready to field your questions. Let’s talk.

To read other blog posts on the errors and illogic of the California Dashboard, click here.