This is a story of connecting the dots, of diagnostic riddles. This is a story about the value of practicing science rather than teaching science. Yogi Berra, Florence Nightingale, and a doctor who cares for the homeless have some guidance for you.

A doctor working at homeless shelters in Boston named Dr. Jim O’Connell noticed an odd pattern. By the end of March, not one person among the hundreds huddling in shelters had gotten sick from COVID-19. In the first week of April, they tested 408 shelter residents, and much to their surprise, 147 tested positive. About 40 percent. Still none of them were symptomatic.

Radiolab brought this story to light in a 20 minute episode dated July 30, titled “Invisible Allies.” The story unfolds as Dr. O’Connell contacts doctors at homeless shelters in other states, and discovers the same thing. No one is getting sick. No one has visible symptoms. Yet many test positive for the virus. The saga led Dr. O’Connell to a brilliant question. What makes homeless people different from the rest of us? As doctors talk with epidemiologists and virologists, brainstorming this riddle, one of those hunches rises above the rest. What if it’s sunshine?

As it turns out, sunshine enables us to synthesize vitamin D. And Vitamin D is directly connected to the regulation of our antibody response. What homeless people gained by being out in the sun so much was stimulation of Vitamin D. And that is what enabled them to avoid the cytokine “storm” – an extreme antibody response — that is understood to be the cause of so many COVID-19 related deaths.

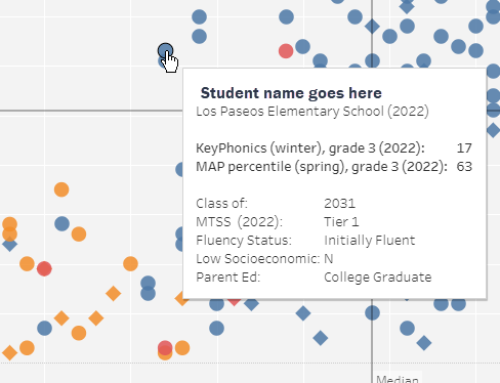

This story is relevant to all of you who are in charge of schools and districts. You, too, have a natural experiment in your hands. You have the ability to gather evidence from your teachers and students, as you start admitting students to classrooms in limited numbers. If you limit students’ movements, especially in elementary schools, can’t you also document who they sit near and play with? Can’t you use that evidence to discover patterns of infection today that will help you decide how to minimize the risk of infection tomorrow?

It isn’t easy. It requires documenting student seating and more. It requires noting who gets sick. It requires brainstorming in search of that brilliant question. It requires forming a hunch based on the patterns you detect. And it requires collaboration so you can validate your hunches.

Florence Nightingale and Yogi Berra both understood the value of paying attention to patterns, and drawing conclusions from the evidence they built.

After all, Florence Nightingale did it for British soldiers during the Crimean War in the 1850s. This was almost a decade before Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister advanced the germ theory of disease transmission. She paid attention. She documented which soldiers died, and why. Using experimental methods, she assembled the evidence that improved hygiene could prevent deaths and improve the rate of recovery of soldiers. She kept careful statistics, and developed visual expressions of them that were entirely original.

Yogi Berra, the great catcher and manager of the New York Yankees ball club in the 1960s, said: “You can see a lot just by looking.” His wise words are a call to open your eyes, and bring some science to the operational side of schooling. It’s also a call to make your school and district admin team a learning organization. If you hope to engender learning among your students, why not begin by making your district admin team a learning organization. Indeed, why not enlist your students to help you, and take on this science experiment together.