Supt. Fred Navarro at Newport-Mesa USD has taken a stand on the question of the quality of evidence. He has told his planning teams to use no bad evidence. That includes demoting the Dashboard, as needed. But why is this prudent and reasonable step noteworthy? It’s unfortunately noteworthy because the CDE has built a Dashboard that produces flawed conclusions from otherwise sound data, and then told site and district leaders to build their plans based on those conclusions. And they’ve failed to point districts toward the higher quality evidence they may already possess.

Supt. Fred Navarro, leader of Newport-Mesa USD

I’ve already written a half dozen blog posts about the logic errors and arithmetic flaws of the Dashboard. I’ve covered logic errors in determining gaps, the fallacy of combining status and change, the mismanagement of English learners as a category, among others. And on January 30, I delivered a presentation to the ACSA Supes Symposium on this topic, together with Supt. Fred Navarro who leads Newport-Mesa USD.

Here’s the point. Flawed evidence should not be the basis of your plans. Flawed evidence misses your strengths and misidentifies your problems of practice. Flawed evidence results in a waste of time designing remedies for misdiagnosed problems. How can good plans result from such a bad starting point? Before you commit your district’s money and people to fixing or improving something that you think is in need of repair, at the very least, confirm your evidence of the problem. Here’s the good news … You can do that with evidence you build from student-level records already in your hands. And there’s technical talent available to help you do this right.

Local control also means you have the freedom to build your own base of evidence

Fortunately, the ethos of our era is local control. It’s a moment when districts are urged to stop seeking the compliant path, and start thinking independently. Lucky timing. Districts are, indeed, free to build their own evidence to plan with. And many have. Over 125 districts accounting for 3,000 schools have joined the CORE Data Collaborative. It costs them a pretty penny (no less than $28,000 a year for the smallest district). Other districts have commissioned our K12 Measures team to build them comparative evidence of their schools’ and districts’ vital signs (by the way, at a far lower cost). But what all these districts have in common is that they can demote the Dashboard, and instead build their LCAPs and SPSAs on a body of evidence of higher quality, using methods of a sounder sort.

(By the way, “evidence” is not the same as data. Data is the raw material from which evidence is built. Just as “truth” is not the same as facts. It’s how you build, and what data you select, combined with the vantage point you view it from, that results in “evidence.”)

You have the potential to build the best evidence for answering the biggest questions from what’s already in your hands: student-level data. Every district possesses student record level data. Even if your district is small, even if your schools enroll less than 300 kids, the raw materials are already in your hands. It is that vault of data, present and past, about your students, their teachers, the resources you’ve given them, and the artifacts of their learning, that can yield insights the Dashboard can never deliver.

Student-level data holds the power to reveal patterns of progress

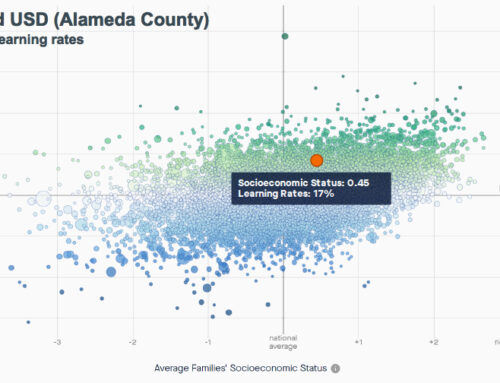

The trick is to organize that data in a way that enables you and your key users to see students’ patterns over time – in fact, over as long a stretch of time as possible. The more evidence, the better. If you can display those patterns for individual student records, you can roll up those results into meaningful units of analysis. The most obvious: graduating class cohorts. If you can show all the students who started school together in the 2010-11 school year, and who are set to graduate in 2023, you can show the variety of outcomes that cohort of students experienced as they advanced through your teachers’ classrooms and schools toward a diploma. (And if you like, you can allow for students’ entering that cohort, or not allow it. But it’s in your control.) That cohort level view is exactly what’s missing from the Dashboard’s interpretation of the CAASPP/SBAC results. And that is one of many reasons why their status-and-change blend results in a lower quality of evidence than the data you can turn into high quality evidence.

The assessment team at Newport-Mesa USD, led by George Knights (back row, left), has built the evidence of the pace of learning for every student.

What student-level assessment data could reveal is the pace of growth. This is what makes Supt. Fred Navarro’s leadership of Newport-Mesa USD so distinct. He presented with me at ACSA’s Superintendent’s Symposium, and told the story of the power of organizing data to measure growth, above all else. For assessing literacy in grades K-6, they use STAR Reading (Renaissance Learning) and Acadience (formerly DIBELS Next) and a customized version of Wonders Close Reading of Complex Text. Then they invest in interpreting this ensemble of assessments to tease out growth estimates, for each and every student. (NWEA’s MAP Growth assessment suite was designed to measure growth, and over 200 California districts rely on them.)

This is the evidence they value most. This is what they use for planning. Whatever your district is using to evaluate student level literacy and numeracy, if the assessments were designed to measure growth and the items are of high quality, you have what you need to build your own evidence base.

The CAASPP/SBAC Results Are Sound Evidence If Viewed From the Right Vantage Point

Does Newport-Mesa’s team use the CAASPP/SBAC data to see where they stand? Sure. But they don’t rely on the Dashboard’s interpretation of it, as this board report of October 2019 reveals. They interpret it as they see fit. The Dashboard’s findings appear nowhere in this 60+ slide presentation.

Here’s a suggestion for you. If you ask your LCAP and SPSA planning teams to tell you what evidence they consider to be the highest quality, and what evidence is of the lowest quality, you’d be getting started in the right direction. If you ask them if they’d like to rely on the highest quality data, and demote the rest, you’d be giving them the freedom they need to do their best thinking, without the distraction of compromised evidence in the way. Should you include the CAASPP/SBAC results? Of course. But the Dashboard’s interpretations of its meaning? Nope. Why not start planning with the only the right evidence on the table?