I’ve recently returned to the side of principals, helping them build site plans that mean something. This is the third year our K12 Measures team has provided support to planners, and I’m moved to say out loud what I’ve kept too quiet in prior years. It is not fair or reasonable to call this “planning.” Principals are not given full control of their resources. Yet they are expected to make measured improvements in the year ahead. I don’t buy it. Authority and responsibility aren’t matched.

Outside the school world, real plans presume that you can choose the people who work for you, and determine within limits what you pay them. Real plans presume you have all the funds available to you to reallocate. Real plans set goals that can be measured during the year, so you know whether you’re on- or off-course. (This applies to the public sector and private sector, to those organizations that produce services and goods.)

Planning in the school world is compromised at the outset by a mismatch of authority and responsibility. Most principals have little say in who works for them. In some districts, seniority rights of staff override the authority of management to assign teachers where they’re most effective. Money is just as gnarly a problem. The only funds that principals get to allocate are Title I funds, which is often less than 15 percent of their school’s operating budget. With such limited control of people and money, is it fair to expect principals to steer their ship according to a plan? Or are districts just expecting principals to row harder next year?

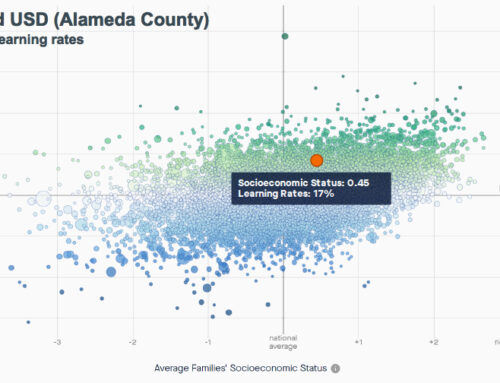

(In California, the California Department of Education hands principals a body of evidence, the Dashboard, a broken instrument that often points leaders in the wrong direction. Click here to read more on the Dashboard’s flaws.)

I’d like these limits to be made clear at the beginning of the planning process. It would help to make it an honest exercise in making the most of the limited things that principals do control, including but not limited to:

- who teaches whom;

- when and how long they teach each subject;

- what subject they teach (yes, even in elementary);

- how teachers teach;

- how principals evaluate teachers;

- how student learning is measured;

- and in high schools, determining the courses offered, and the level of rigor of those courses.

What would no longer be asked of principals is the hocus-pocus magic trick of forecasting changes in test scores. It has become an exercise in faith-based pseudo-planning, and resembles, at best, a pledge to work hard to make more and higher quality learning occur.

And for those districts that are ready to give principals more authority, especially budget and hiring authority, I would only ask that they prepare principals well before giving them the reins, and with smart technical support after they do. These districts could make planning really mean something. (See this policy paper from PACE on the experience of Oakland, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Seattle and St. Paul in giving principals more control of school resources and more responsibility for results.)

For the rest of the districts that remain committed to centralized management, please stop expecting principals to write a plan and then expect them to make it work. Just admit you’re not giving them control over their staff or their operating budget. And then urge them to invest in the factors they do control:

- planning their use of time

- deciding who teaches whom

- managing their assessments

- interpreting the evidence of student learning

Who knows? Focusing on what’s real might even lead to plans becoming a reliable navigational instrument for the year ahead.